(Mahnoor Rahat)

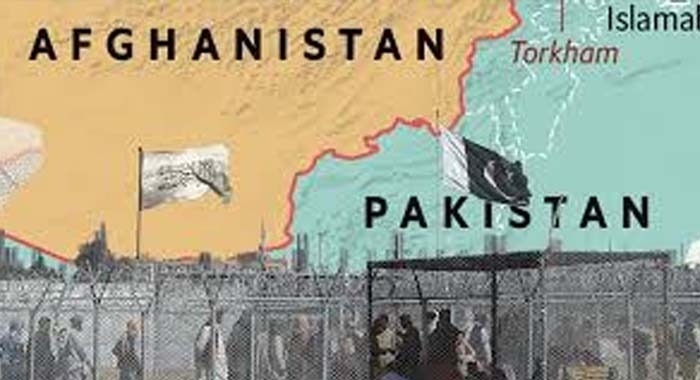

The simmering tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan are once again reaching a critical point, threatening to destabilize not only their own borders but the broader South and Central Asian region. What appears on the surface as a bilateral dispute is, in reality, a complex interplay of security dilemmas, economic stakes, and geopolitical ambitions. The repercussions of inaction could reverberate far beyond Islamabad and Kabul, affecting trade, investment, and regional security networks.

In recent discussions with Shamim Shahid on The Khyber Chronicles, the multifaceted dimensions of this crisis were laid bare. Shahid emphasized that the challenges extend beyond traditional diplomacy, highlighting the role of militant networks, economic consequences, and the urgent need for coordinated regional mediation.

Russia has emerged as a particularly active interlocutor, offering to mediate between the two neighbors. Moscow’s intervention is more than a diplomatic gesture; it reflects the strategic calculus of a global player invested in regional stability. Alongside China, Russia has expanded its economic footprint in Afghanistan, investing in infrastructure and trade corridors. Yet, prolonged bilateral tensions threaten to undermine these projects. Disrupted trade routes and stalled investments would not only stall Afghanistan’s fragile economic recovery but could also imperil international interests in South and Central Asia.

Security concerns are equally pressing. Militant networks, particularly the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), remain influential, exploiting porous borders and fragile governance. While the Afghan Taliban have largely contained TTP activity within Afghanistan through political and diplomatic measures, Pakistan continues to face insurgent activity in North Waziristan, Lakki Marwat, and Bannu. Cross-border attacks, whether deliberate or opportunistic, risk destabilizing local populations, eroding public trust, and complicating broader bilateral relations.

Shahid noted that Pakistan’s security strategy is evolving in response. Provincial authorities are gradually reclaiming counter-terrorism responsibilities from the military, transferring them to the Counter-Terrorism Department (CTD) and local police forces. This shift, first trialed in 2012, demands careful coordination with federal authorities. The success of these reforms hinges not only on institutional capacity but also on political backing and public trust. Without these elements, even the most sophisticated counter-terrorism measures will fall short.

The economic dimension adds another layer of urgency. Key trade arteries such as the Chaman and Torkham crossings are lifelines for regional commerce. Any disruption threatens to reroute trade through alternative corridors, bypassing Pakistan entirely. The potential fallout is severe: decreased revenue, weakened regional influence, and heightened economic insecurity for communities on both sides of the border. In Shahid’s analysis, the economic consequences of sustained tension could outweigh immediate political disputes, making urgent dialogue imperative.

Regional powers have recognized the stakes. Iran, Turkey, Qatar, and Russia have all attempted mediation, reflecting both concern and opportunity. Yet, these efforts cannot succeed without genuine political will from Islamabad and Kabul. Individual diplomatic initiatives, while valuable, are insufficient on their own. What the region needs is a coordinated, multilateral approach that combines dialogue with actionable security and economic strategies.

Failure to act carries real consequences. Rising extremism, cross-border violence, and economic stagnation could trigger a cycle of instability with regional ramifications. The threat is no longer contained within national borders; it has become a shared challenge, one that could shape the trajectory of South and Central Asia for years to come.

The path forward demands balance. Diplomatic engagement must be coupled with security reforms and regional cooperation. Governments must empower local authorities and law enforcement, while simultaneously addressing the influence of militant networks. Public trust is the linchpin without it, both governance and security efforts risk collapse.

Pakistan and Afghanistan stand at a precarious juncture. The willingness of regional actors like Russia, China, Iran, and Turkey to mediate offers a narrow window of opportunity. But long-term stability will depend on more than external facilitation. It requires a concerted commitment to dialogue, a credible security framework, and a shared vision of economic and political cooperation. Only through such a comprehensive approach can the region hope to transform tension into trust and fragility into resilience.

In a world increasingly shaped by interconnected threats, the security and prosperity of Pakistan and Afghanistan are inseparable from that of their neighbors. As Shamim Shahid underscores, the choices made today will determine whether South and Central Asia remains a corridor of conflict or a bridge to stability and growth. The time to act is now.