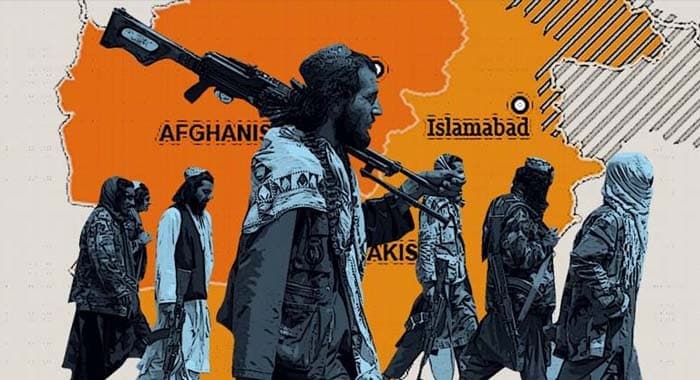

In the first half of 2025 alone, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) claimed over a thousand attacks, with more than 300 incidents in July, underscoring the scale of its resurgence across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and southern Punjab. Beyond the rising toll of violence, however, lies a more insidious transformation. The TTP, once defined primarily by its hardline pursuit of Shariah, is now rebranding itself as the defender of Pashtun identity blending religious militancy with ethnonationalist narratives to project itself as a guardian of the Pashtun nation.

Born in 2007 out of a coalition of militant factions in Pakistan’s tribal belt, the TTP initially married a rigid Deobandi ideology with transnational jihadist networks. Its founding charter identified three missions: enforcement of Shariah, unity with the Afghan Taliban against foreign forces, and resistance against Pakistan’s security institutions. For years, its campaigns were steeped in religious justifications, from fatwas against Pakistani media to suicide bombings framed as acts of jihad.

Sustained military operations, U.S. drone strikes, and internal fractures between 2014 and 2018 brought the group to a historic low. Yet, by 2019, signs of revival surfaced — renewed attacks, mergers with splinter factions, and a sharpened propaganda apparatus. The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 2021 accelerated this resurgence, providing both sanctuary and ideological validation.

What is striking today is the shift in tone. While religion remains central, the TTP increasingly overlays its militant project with narratives of tribal honor, ethnic grievances, and Pashtun solidarity. This mirrors the Afghan Taliban’s fusion of Islamist and ethnonationalist identities a model the TTP appears intent on replicating. Several converging dynamics have pushed the TTP toward this hybrid rebranding.

Theological delegitimization has weakened its religious authority. The state now officially designates the group Fitna al-Khawarij, drawing on Islamic history to depict it as deviant and illegitimate. Prominent clerics such as Mufti Taqi Usmani have echoed this framing, undercutting the TTP’s claim to religious purity.

Recruitment competition from the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) has also forced adaptation. ISKP has expanded its footprint through aggressive multilingual propaganda, positioning itself as ideologically “purer” than the TTP. To maintain relevance, the TTP has broadened its appeal.

Finally, the salience of ethnic politics has grown. The rise of Baloch insurgent violence has demonstrated the resonance of identity-based narratives. The TTP, too, has increasingly found that ethnic slogans may travel further than religious decrees.

The TTP now seeks to frame itself as a representative of Pashtun society. Its Pashto-language magazine Mujallah Taliban condemned the killing of peace activist Molana Khan Zeb, despite his vocal criticism of militancy, using the incident to call for Pashtun unity against “state-engineered chaos.” Speeches by commanders like Ilyas Malang Bacha during Eid in Bajaur, propaganda videos such as Jihad ka Musafir, and visuals of militants attending jirgas all aim to depict the group as a natural part of tribal life.

The contradictions are stark. The same group that claims to protect Pashtun interests continues to assassinate tribal elders, Aman Lashkar leaders, and peace committee members, reframing such killings as punishments for “betrayal.” Tellingly, the TTP has shifted away from branding its opponents as apostates, instead labeling them “spies” a calculated move to recast its violence in political and ethnic terms rather than theological ones.

Under the leadership of propagandists like Muneeb Jutt, the TTP’s media strategy has entered the digital age. AI-generated posters circulate on Telegram and X, depicting destroyed homes, civilian casualties, and imagery of Pashtun resilience. These are paired with popular jihadi nasheeds like Shaheen Jawan and Markay hain Tez Tar, exploiting familiar cultural forms to maximize reach.

The group also links local grievances to broader narratives of neglect, citing mortar fire in Khyber and Tank, or governance failures during Swat’s floods, as evidence of systemic injustice. In doing so, the TTP seeks to monopolize grievance politics and position itself as the voice of marginalized communities.

The ethnic reframing is not without peril. By invoking historic resistance figures like Faqir Ippi and casting the Durand Line as a colonial scar, the TTP is embedding itself within a broader tradition of Pashtun struggle. Communities that cooperate with the state, whether through Aman Lashkars or police units, face acute risks — illustrated by the suspension of 42 Orakzai police officials who refused anti-terror operations, an act the TTP publicly praised.

Meanwhile, recruitment is no longer confined to the tribal belt. The group has expanded into southern Punjab, targeting Siraikis and Baloch youth while glorifying Punjabi militants such as Habib ur Rehman as defenders of both the ummah and the tribal nation. This strategy hints at a widening base beyond Pashtun borders, increasing the risk of cross-ethnic insurgency.

This evolution makes clear that kinetic operations, though vital, are insufficient. Recent successes in disrupting cells in Hangu, North Waziristan, Bajaur, and Orakzai have not blunted the narratives sustaining militancy. Countering the TTP requires a dual-track strategy.

Counter-narratives must directly address both the religious and ethnic strands of TTP propaganda. Particular attention should be paid to dismantling the group’s invocation of historical fatwas and its claim to Pashtun guardianship. Digital disruption is essential. The group’s AI-driven propaganda campaigns and pseudo-accounts on social media platforms must be monitored, traced, and dismantled.

Community engagement is critical. Transparent forums and jirga-style hearings to review incidents of civilian harm can restore trust, ensuring that grievances are addressed by the state rather than exploited by militants. Institutional reforms to strengthen provincial autonomy and local decision-making in security affairs will further reduce perceptions of centralized interference, a theme frequently weaponized by TTP propaganda.

The TTP’s transformation from a jihadist vanguard into an insurgency draped in ethnic identity marks a dangerous new phase. Its hybrid narrative seeks to erode the bonds between the state and society, embedding militancy within the very language of identity and grievance. Pakistan’s challenge is to blunt not only the TTP’s military capability but also its ability to claim legitimacy as the defender of the Pashtun nation. Unless both dimensions are addressed, the group’s evolving strategy risks entrenching a broader, ethnicized insurgency that will be harder to contain.