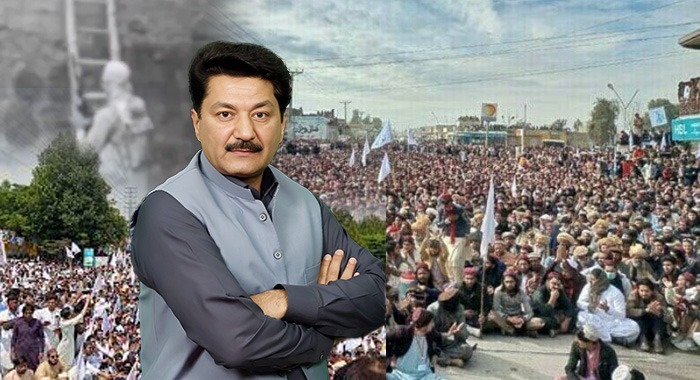

Fida Adeel

The delicate balance between peace and conflict in Pakistan’s tribal districts is once again under scrutiny as recent developments in Khyber, Bajaur, and other tribal areas highlight the complex interplay between local Jirgas, militant presence, and state security policy. Against the backdrop of evolving Pak-Afghan relations, the path forward whether through dialogue or decisive military action—remains a contentious debate with no easy answers.

The state of Pakistan has made its stance clear: there will be no negotiations with any armed group in the future. If peace and security talks are to take place, they will be strictly between governments. This policy stems from the bitter lessons of the past, particularly the failed negotiations between the Taliban and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which only resulted in renewed violence.

The local reality, however, is far more complex. In recent months, tribal Jirgas have emerged as parallel peace initiatives. In Khyber’s Tirah Valley, a large procession of over 8,000 residents engaged in talks with militants, ultimately reaching a negotiated settlement that has brought temporary calm. Similar efforts are underway in Bajaur, though without success so far. Militants have rejected demands from the Jirga to vacate populated areas, insisting instead that they are locals with a right to remain. Security assessments suggest otherwise, pointing to the presence of Afghan nationals among the ranks of these militants. Identification of slain fighters has repeatedly confirmed cross-border infiltration.

The stakes are high in Bajaur, where fears of a military operation loom large. Security sources have urged tribal elders to either remove the militants themselves or allow the security forces to clear the area. But such demands place local communities in an impossible position. Residents are often coerced into hosting militants sometimes up to 15 or 20 armed men arrive at a house demanding food—and refusal risks violent reprisal. This dynamic leaves ordinary people “sandwiched” between militants and the state, lacking both the resources and the armed capability to confront such groups.

This dilemma is compounded by memories of past operations, which displaced thousands from North and South Waziristan, Bajaur, Khyber, Mohmand, Swat, and other districts. Entire families were forced into tents or rented accommodations, children’s education was disrupted, and livelihoods were destroyed. Understandably, communities are deeply reluctant to endure another round of mass displacement.

Public sentiment reflects a divided reality: while there is strong opposition to blanket operations, there is also recognition that militants are a primary source of instability. People desire peace but not at the cost of indiscriminate destruction. Calls for any military action to be targeted and precise minimising civilian casualties are growing louder. The misuse or misdirection of drone strikes and quadcopter attacks, which have sometimes harmed women and children, has only deepened mistrust.

The ceasefire in Khyber is now seen as a litmus test. If it holds, the approach of dialogue through Jirgas may be extended to other regions. If it collapses, pressure for military action will intensify. In either case, political unity remains elusive; parties are divided, and without consensus, sustained peace efforts will face severe challenges.

These local security dynamics unfold in parallel with significant diplomatic manoeuvres. The much-anticipated visit of Afghan Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi to Pakistan was postponed due to a technical obstacle: under UN sanctions, Islamabad must seek special permission for his entry. The visit was overshadowed by the arrival of Iranian President Dr. Masoud Pezeshkian, which absorbed official attention.

Preparations for the Afghan delegation’s visit were extensive, with agreed agendas, draft MOUs, and confirmed participation lists. Meetings in Kabul between Pakistani ministers Ishaq Dar and Mohsin Naqvi and senior Afghan officials followed by high-level discussions in Beijing covered trade, security, and most notably, the TTP issue. Engagements with influential figures such as Sirajuddin Haqqani signalled an effort to address militancy as part of a broader Pak-Afghan dialogue.

Yet, the same paradox persists both domestically and diplomatically: peace processes and military readiness continue side by side, each seen as a contingency for the other’s failure. History warns that ceasefires have often allowed militants to regroup. At the same time, operations if poorly targeted can breed new grievances and instability.

The weeks ahead will determine whether Jirgas in Bajaur and other districts can succeed where force has failed, or whether Pakistan will once again be drawn into an operational cycle it has long sought to break. Either way, the stakes both for local communities and for Pakistan’s wider security could not be higher.