The rumours of an Indo-Taliban nexus seeking to weaponize water against Pakistan have proven to be an undeniable fact as Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada has ordered the immediate construction of a dam on the Kunar River — a move that experts warn could trigger a new wave of regional tension over shared water resources.

According to Taliban Minister for Energy and Water, Abdul Latif Mansoor, the directive was explicit: Afghanistan’s Ministry of Energy and Water must begin construction “as soon as possible,” without waiting for foreign companies. Instead, Akhundzada instructed officials to sign contracts with domestic firms, declaring that “Afghans have the right to manage their own waters.”

The Kunar River, which originates in Pakistan’s Chitral district before flowing 482 kilometres through Afghanistan’s Kunar province and merging with the Kabul River, sustains vast agricultural and hydro-power needs on both sides of the border. Its waters are vital to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s irrigation and power generation systems — meaning any alteration upstream could have severe consequences for Pakistan’s food and water security.

Rising Sensitivities in Pakistan

The Taliban’s renewed push to build dams on the Kunar River comes amid heightened mistrust and escalating border friction between Kabul and Islamabad. The two countries lack any formal water-sharing treaty, relying instead on informal and historical practices.

Pakistani officials view the unilateral move as provocative, especially after reports emerged last year that Islamabad was studying engineering options to divert the Chitral River — before it enters Afghanistan — toward the Swat River to secure its water interests.

Former provincial minister Jan Achakzai had earlier cautioned that unilateral dam construction by the Taliban would be perceived as an openly hostile act, potentially leading to direct confrontation. Similarly, Baloch and regional analysts have linked the Taliban’s new “water policy” with India’s long-term strategy to squeeze Pakistan’s river flows — a strategy already evident in New Delhi’s unilateral interventions along the Indus basin.

Despite these concerns, Mansoor has continued to echo Akhundzada’s defiant tone. In an interview with Shamshad TV, he said: “If we do not build a dam on the Kunar now, we never will.” He added that the Kunar basin offers unparalleled hydropower potential and accused “certain neighbours” of opposing Afghanistan’s control over its natural resources.

A Broader Regional Water Game

Taliban officials have also invoked disputes with Central Asian republics, asserting that those states have long exploited Afghan waters while blocking Kabul’s efforts to do the same. Mansoor cited the Qosh Tepa Canal as one such project that seeks to reclaim lost water rights.

He claimed that during his visit to Turkmenistan, officials urged adherence to Soviet-era water-sharing accords — an appeal the Taliban flatly rejected, insisting that “agreements signed under occupation” were void. The minister clarified that the Taliban recognise only one formal water treaty — with Iran over the Helmand River — while construction elsewhere “faces no restrictions.”

China’s Interest, India’s Shadow

Even as Akhundzada’s decree accelerates the dam’s timeline, the Taliban face financial hurdles. Mansoor lamented the absence of investors, stating that both local and foreign financiers had failed to commit funds for ongoing water projects.In August 2024, Afghanistan’s Ministry of Energy and Water claimed that a Chinese energy consortium had shown interest in investing in three hydro-power dams — Shal, Sagi, and Sartaq — on the Kunar River. These projects, Mansoor said, could eventually allow Afghanistan to export electricity to neighbouring countries.

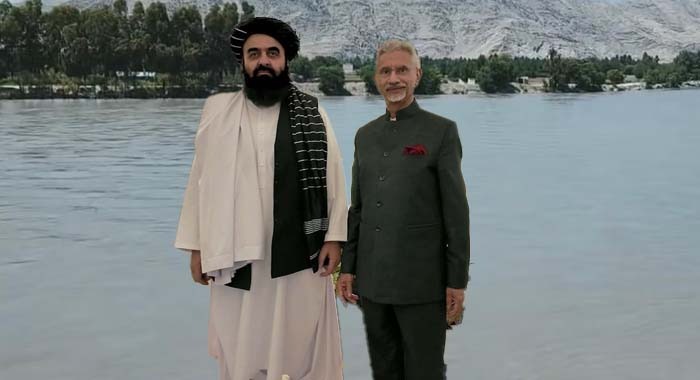

However, analysts note that India’s influence looms large behind Kabul’s new water assertiveness. New Delhi’s past collaboration on Shah Toot and Salma dams, coupled with its financial and technical leverage in Afghanistan, has raised serious alarm in Islamabad. Pakistani strategists now warn that the Indo-Taliban cooperation could be the next chapter of India’s broader campaign of “hydro-logical encirclement” — this time from the west.

Islamabad’s Red Line

Pakistan has repeatedly stressed that its water sources are a national red line. Officials have warned both India and Afghanistan that any attempt to restrict or manipulate trans-boundary flows will be treated as an act of aggression.

For Islamabad, the Taliban’s latest move is not merely an engineering project — it’s a geopolitical signal that a new kind of hybrid confrontation may already be unfolding, one in which rivers replace rockets as weapons, and dams become tools of regional coercion.