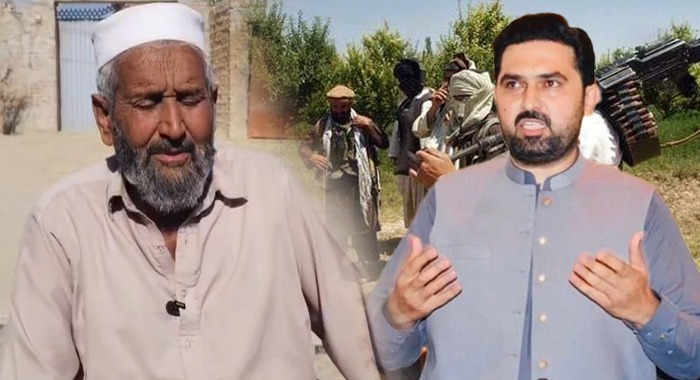

A Father’s Unanswered Plea

“I am Umar Ayaz from Kot Brarra,” says the weary voice on the phone. “My daughter was martyred in the Ramadan blast. In this heinous act of terror, our house collapsed that night, the entire neighbourhood turned to rubble, but no help ever came.”

Almost over a year later, Umar still lives in a half-built structure raised through borrowed money. The blast that tore through his village in Bannu district not only took his child but also exposed how fragile and forgotten life remains in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s conflict-hit belt. “We heard that compensation was approved,” he says, “but we never received a rupee. If the government can’t help, at least tell us that honestly.”

For residents like Umar, these are not just tales of personal loss; they are proof of how governance has receded behind political priorities.

A Pattern of Neglect

Umar’s story mirrors that of many across KP. In Mohmand, families of terror victims tell similar stories; promised aid, missing payments, and vanished officials. This, despite the fact that the province has received between Rs600 to 700 billion from the federal government under anti-terror and rehabilitation allocations.

The money was meant to rebuild homes, compensate victims, and strengthen frontline policing. Instead, it has vanished into a maze of paperwork, politics, and patronage.

Misplaced Priorities in Peshawar

When Sohail Afridi assumed office as Chief Minister, his first administrative decision was symbolic — but costly. He returned the province’s bulletproof vehicles to the federal government, declaring that “KP stands on its own feet.”

For his party, it was a gesture of defiance. For the police, it was a signal of abandonment.

Those vehicles were not for luxury; they were essential protection for officers leading anti-terror operations in some of the country’s most dangerous districts. Afridi’s decision, described by many in the security establishment as “reckless,” laid bare his government’s preference for optics over security.

Politics First, People Later

The crisis runs deeper than one decision. KP today stands at a dangerous crossroads — struggling with terrorism, extremism, hate-driven politics, poverty, unemployment, and a resurging drug trade.

The epicentre of that narco-network is Tirah Valley, part of Khyber district, the very region the Chief Minister calls home. It is here that militancy, narcotics, and smuggling overlap into a lethal triad threatening Pakistan’s internal stability.

Yet for Sohail Afridi, political symbolism outweighs ground realities. His speeches centre on the release of his party leader, Imran Khan, from Adiala Jail, while his administration overlooks the daily threats faced by police, teachers, and ordinary civilians across KP.

The Cost of Political Theatre

In a province where bombings still shatter markets and checkpoints, the people’s patience is wearing thin. From Bannu to Mohmand, the demand is not for slogans but for safety, compensation, and leadership that can distinguish governance from campaigning.

For now, however, KP’s governance model appears caught in a familiar loop — one where politics dictates policy, and where the victims of terror remain unseen, unheard, and uncompensated.

Pakistan’s war on terror cannot be won through slogans or symbolic defiance. It requires provincial leadership that values institutions over parties and people over politics.

The federal government has fulfilled its financial commitments, but unless those funds reach the ground, unless fathers like Umar Ayaz see justice and relief, the cycle of resentment will deepen.

The time has come for KP’s rulers to choose: serve their people or serve their politics. For the people of Bannu, Mohmand, and Khyber, that choice is not ideological. It is a matter of survival.