When Kabul fell to the Taliban in August 2021, few nations felt the tremors more directly than Pakistan. For Islamabad, the Taliban’s resurgence was not merely a shift in Afghanistan’s political landscape it was the return of a force with deep ideological, cultural, and historical ties to its own frontier regions. Yet, amid global finger-pointing and renewed regional volatility, Pakistan has remained the most critical bulwark for stability along the world’s most restless border.

The Taliban’s ideological roots stretch into the Deobandi movement that emerged in the late 19th century in India and found fertile ground in Pakistan’s religious seminaries during the Afghan-Soviet War. Many of the Taliban’s senior figures, including their current chief Haibatullah Akhundzada, were educated in Pakistani madrassas after fleeing Soviet occupation and later returned to Afghanistan as mujahideen.

Pakistan, at that time a frontline U.S. ally, played a decisive role in supporting the Afghan resistance against Soviet forces. When the Taliban established the Islamic Emirate in 1996, Islamabad alongside Saudi Arabia and the UAE recognised their regime, hoping for a stable Afghanistan that would serve as a strategic buffer. However, after 9/11 and the fall of the Taliban, Pakistan became a key partner in the U.S.-led “War on Terror,” even handing over several Taliban leaders to Washington. In later years, Islamabad endorsed a political settlement in Afghanistan and supported the U.S.-Taliban peace deal, demonstrating its consistent pursuit of regional stability.

But while Pakistan diplomatically backed reconciliation, its borderlands bore the brunt of the chaos that ensued. The Taliban’s war with the Northern Alliance in the 1990s spilled across the Durand Line. Pashtun tribes in Pakistan’s tribal belt linked to Afghan Pashtuns by ethnicity and faith offered sanctuaries and logistical help, entrenching cross-border militancy. Training camps emerged in ex-FATA, where fighters were prepared for battle in Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s fall in 2001 and reemergence in 2021 mirrored the ebb and flow of militancy in Pakistan’s own frontier. When Kabul once again fell to the Taliban, celebrations erupted in parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, where some viewed it as divine justice after two decades of U.S. occupation. Social media teemed with quotes attributed to Mullah Omar, proclaiming divine victory, and sermons across rural mosques echoed with praise for “Islamic triumph.”

Yet, the ideological euphoria did not unify Pakistan’s political spectrum it exposed deep divides. For religious parties such as Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (Fazl) and Jamaat-e-Islami, the Taliban’s victory was hailed as a vindication of faith-based politics. The JUI-F, historically tied to Afghan Islamists, gained electoral strength in the 2021 KP local government elections, particularly in border districts.

In contrast, secular Pashtun nationalists like the Awami National Party (ANP), long viewed as anti-Taliban and sympathetic to the former Ghani administration, sounded the alarm. In a Central Executive Committee meeting in September 2021, ANP leaders warned that terrorism, extortion, and targeted killings were once again haunting KP and Balochistan.

Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), then in power, faced criticism for advocating talks with the Taliban, a stance that earned him the nickname “Taliban Khan” among detractors. Meanwhile, JUI-F chief Maulana Fazlur Rehman openly called on the world to recognise the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan a demand Islamabad approached with caution.

The most direct impact of the Taliban’s return was felt through the resurgence of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Sharing a Deobandi ideology and a long history of cooperation, the Afghan Taliban’s success emboldened their Pakistani counterparts. Many TTP members released from Afghan prisons after August 2021 regrouped across the border, renewing attacks in ex-FATA and KP.

Between August and December 2021 alone, the TTP claimed over 130 attacks including ambushes on security forces and extortion in urban centres like Peshawar. Pakistan’s then interior minister Sheikh Rasheed confirmed that militants were collecting extortion money even in provincial capitals. Terror-related casualties rose from 162 in 2018 to 365 in 2022, with over 50 percent of all national incidents concentrated in KP.

The Afghan Taliban’s refusal to act against the TTP despite repeated assurances severely strained relations. Pakistan engaged the Haqqani Network to mediate talks, during which the TTP declared a temporary ceasefire while Islamabad released some prisoners. However, the group’s core demands including reversal of FATA’s merger with KP and unconditional pardons were non-negotiable. When talks broke down, the TTP ended the ceasefire by assassinating anti-Taliban leader Idrees Khan in Swat in September 2022.

Since then, the group has intensified abductions, extortion, and targeted killings, spreading fear across KP’s valleys and border towns. Prominent figures, including provincial minister Atif Khan, have received threats demanding millions in ransom. Public outrage has surged, with large anti-terror rallies across ex-FATA demanding decisive state action.

Islamabad, once patient and diplomatic, is now increasingly assertive. Repeated cross-border attacks have pushed Pakistan to demand that Kabul rein in the TTP or face consequences. While the Taliban government insists it will not allow its soil to be used against neighbours, the facts on the ground suggest otherwise. The situation today is far more volatile than during the Taliban’s first regime (1996–2001), when the TTP did not exist and anti-Pakistan sentiment among Afghan factions was far less pronounced.

Parallel to terrorism, the narcotics trade remains a hidden but powerful destabilizer. Afghanistan continues to produce nearly 85 percent of the world’s opium, and roughly 45 percent of its illicit output flows through Pakistan — primarily via Balochistan. Drug profits have long funded militant activities, including those of the TTP and criminal networks in ex-FATA.

Pakistan’s Anti-Narcotics Force (ANF) has mounted an aggressive response. Between August 2021 and April 2022, it conducted 371 operations and seized drugs worth an estimated US$3 billion. Yet the challenge remains monumental. Local authorities reported record seizures in late 2021 and early 2022, proving that traffickers are exploiting Afghanistan’s instability and Pakistan’s mountainous terrain.

The Taliban, once known for briefly banning opium in 2000, now rely heavily on drug revenues reportedly earning up to US$400 million annually from the trade before 2021. Pakistani officials, including former Minister for Narcotics Control Akbar Durrani, have warned that continued Afghan instability will aggravate Pakistan’s domestic drug crisis, where the number of addicts has risen from seven million in 2015 to nine million in 2021.

It is easy for observers to forget that Pakistan has been both the victim and the first responder in the world’s longest war. For over four decades, Pakistan has housed millions of Afghan refugees, fought multiple insurgencies, and absorbed economic and human losses far exceeding those of any Western ally. Despite this, Pakistan has not succumbed to extremism; its military remains one of the few national institutions in the region capable of sustained counterterror operations.

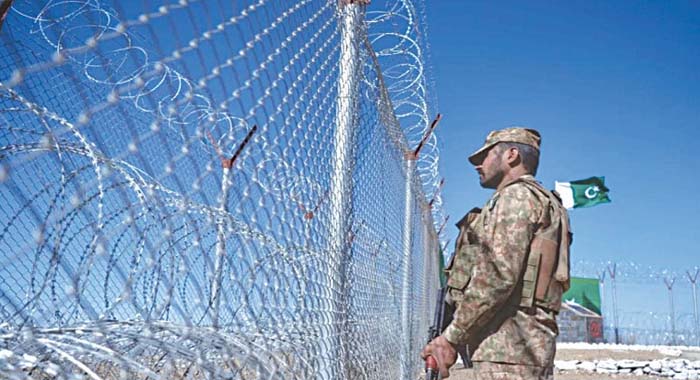

The fencing of the Afghan border, intelligence-driven crackdowns, and diplomatic outreach to Kabul are part of Islamabad’s multidimensional strategy one that balances firmness with dialogue. Unlike many regional players, Pakistan seeks not dominance but peace a stable Afghanistan that no longer exports terror, drugs, or refugees.

Pakistan’s border regions have always been the first to feel the tremors of Afghan instability. Yet the state has endured militarily, politically, and morally. The Taliban’s rise may have reignited old fires, but Pakistan stands firm as the region’s last line of order. The challenges of extremism, narcotics, and cross-border militancy are immense, but so is Pakistan’s resilience.

For decades, the world has looked to Pakistan to contain chaos it did not create. That responsibility continues and so does Pakistan’s resolve. On a frontier where ideology, violence, and commerce collide, Pakistan remains a nation tested by fire, but never defeated by it.