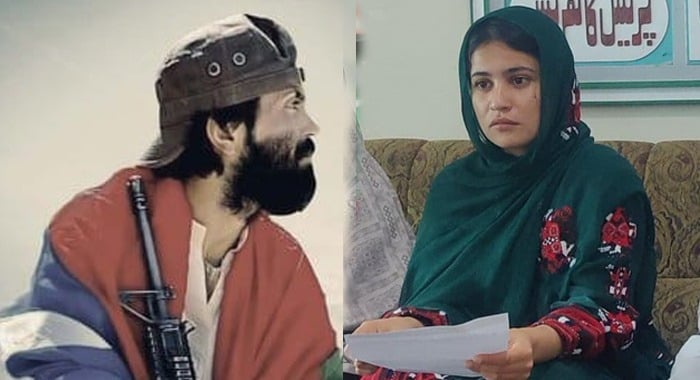

For months, Gulzadi Baloch, a leading voice of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), rallied behind the slogan of enforced disappearances, insisting her brother, Abdul Wadood Satakzai, was abducted by the state. But what BYC framed as a case of victimhood was ultimately exposed as something else entirely: her brother had not vanished into custody, but into militancy, joining the BLA’s Majeed Brigade, where he was later killed in an armed clash during Operation Dara Bolan.

In an official statement, the BLA openly acknowledged that the young man was part of its ‘fidayeen’ (suicide bombers) squad, and he was killed while attempting a coordinated terrorist assault. Days later, the international journal Modern Diplomacy published a report revealing that the individual portrayed as a “victim of enforced disappearance” was, in fact, a key player in a violent militant operation.

This is not an isolated case. Multiple investigations now point toward a recurring pattern: individuals who are publicly labeled as “missing” under the BYC’s narrative later emerge in combat fatigues, serving under proscribed insurgent groups. A recent report by Pakistan Today listed dozens of such cases, where so-called missing persons were later traced back to militant training camps or discovered among the ranks of insurgent outfits.

According to the investigative outlet Policy Wire, this tactic functions as a “double-edged sword”: on one hand, it maligns state institutions with baseless accusations; on the other, it provides insurgent groups with public sympathy, effectively aiding their recruitment campaigns.

The real victims, however, are those families whose loved ones are genuinely unaccounted for. The louder, misleading narratives drown out their pleas, diverting national attention toward false claims, often involving individuals who are later found wielding weapons in militant strongholds.

This weaponized narrative widens the trust deficit between civil society and the state, undermines serious investigations, and enables militant networks to continue their violence under the guise of “resistance”.

The case of Gulzadi Baloch is a glaring example. While she demanded justice in front of cameras and claimed victimhood, she never disclosed how or why her brother’s body was found at the site of a direct armed confrontation. It raises critical questions: How long will platforms like BYC continue to adopt such claims without verification? And how long will sections of the media continue to give these stories unchallenged airtime, out of ignorance or selective bias?

Truth may be delayed—but it cannot be denied. The end of this case demonstrates, unequivocally, that there is a vital difference between a “missing person” and a “militant.”

If genuine victims in Balochistan are ever to receive justice, we must begin by scrutinising and dismantling narratives that present terrorism cloaked in the language of human rights.