(Shamim Shahid)

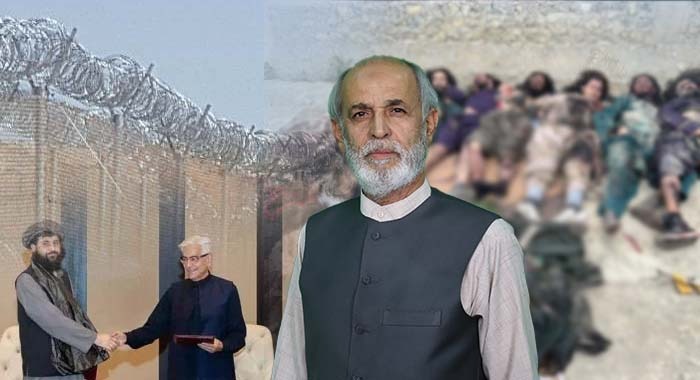

The Istanbul talks, currently underway between Pakistan and Afghanistan, mark the second and perhaps the most crucial phase of negotiations between the two uneasy neighbours. Convened on October 25, the three-day dialogue was expected to bring clarity on bilateral security concerns and the resurgence of cross-border militancy. Yet, despite the presence of high-level delegations and mediation from Turkey, Qatar, Iran, and China, no significant progress has been achieved so far.

The reality, as it stands, is that the negotiations are deadlocked. Both sides remain entrenched in their positions. Pakistan insists that recent terrorist incidents on its soil have direct links across the border, while the Afghan delegation firmly denies any involvement. This rigid stance from both capitals has turned the Istanbul table into a theatre of repeated claims and counterclaims rather than constructive engagement.

Pakistan has reportedly presented evidence to the Afghan side pointing toward the presence and activities of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) elements inside Afghanistan. Yet, the Afghan delegation has neither accepted responsibility nor shown flexibility on the matter. Instead, Kabul has urged that Pakistan should engage directly with the TTP for talks a proposition that Islamabad has already tried and found untenable after repeated breaches of previous agreements.

The heart of the problem lies in mutual mistrust and the absence of political will. While Pakistan seeks tangible cooperation in curbing cross-border militancy, Afghanistan demands an open border and greater trade facilitation, portraying Pakistan’s security measures as restrictions on civilian movement. The deadlock is not merely over territory or border management; it is over recognition, responsibility, and regional stability.

This situation is not new. History is replete with moments when Pakistan has accused Afghanistan of harbouring militants, while Kabul has countered by blaming Islamabad for interference in its internal affairs. The story goes back decades even to the mid-1990s, when incidents like the Dudh Sanzab explosion in 1995 were hastily blamed on Afghan nationals, sometimes even before proper investigations could confirm facts. Such blame games, rooted in political expediency and emotional rhetoric, have kept both nations trapped in cycles of accusation and denial.

The mediators Turkey, Qatar, Iran, and China now face the difficult task of steering these talks away from confrontation and towards compromise. For the international community, the Istanbul process represents not merely another diplomatic ritual but a test of whether Pakistan and Afghanistan can finally move beyond suspicion and chart a path of cooperation.

However, optimism remains fragile. Ordinary people on both sides of the Durand Line are weary of conflict and desire peace. They watch these negotiations closely, hoping that this phase in Istanbul does not become another missed opportunity. The stakes are higher than ever: the failure of this dialogue could not only deepen mistrust but also widen the operational space for non-state actors who thrive on instability.

If both governments continue to view each other through the lens of hostility, the real victims will be neither Islamabad nor Kabul, but the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, and Afghanistan’s border provinces those who have suffered the most from four decades of war and insecurity.

In the end, the Istanbul talks have revealed two truths: one, that the desire for peace exists; and two, that it remains hostage to politics, pride, and past grievances. Whether this dialogue evolves into genuine cooperation or sinks into yet another stalemate depends on the courage of both nations to listen truly listen to one another for the first time in years.

To watch the podcast click on the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gi7KrEXUKrg