Water in South Asia has moved far beyond being a shared natural resource it has become a decisive tool of power, politics, and pressure. As India tightens its grip over Afghanistan’s river systems, particularly the Kabul River Basin, a new front is emerging in regional geopolitics one that directly threatens Pakistan’s water security, agricultural stability, and long-term sustainability.

For years, India has quietly financed and engineered Afghanistan’s water infrastructure, portraying these ventures as development initiatives. In reality, these projects are part of a calculated design to reshape the region’s hydro-political balance and curtail Pakistan’s downstream water flow an extension of the very tactics India has employed under the Indus Waters Treaty.

Recent developments confirm that the Taliban government has formally requested $1 billion in Indian investment for new water projects, signalling a continuation of Indo-Afghan collaboration even after the political shift in Kabul. This alliance underscores India’s persistent ambition to gain strategic depth in Afghanistan not through troops or trade, but through control over water, the region’s most critical and finite resource.

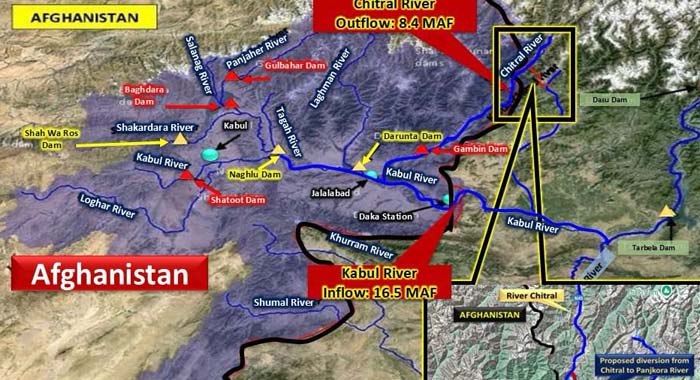

India has already funded or planned several dams across the Kabul River and its tributaries, including Naghlu, Darunta, Shah wa Aros, Shahtoot, Gat, Kajab, Band-e-Khwar, and Gambiri. Of these, the Shahtoot Dam a $250 million project poses the most serious implications for Pakistan. It is designed to meet Kabul city’s water demand but will simultaneously reduce water inflow into Pakistan by millions of acre-feet. Estimates suggest that, collectively, these projects could cut Pakistan’s annual share by up to 16 million acre-feet, striking directly at the heart of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s agrarian lifeline.

The Kabul River sustains the fields, economy, and livelihoods of KP. Any disruption in its flow would unleash cascading effects: Agricultural yields would plummet in Peshawar, Nowshera, and Charsadda, risking food insecurity. Hydropower generation at Warsak Dam would decline, intensifying the province’s energy shortfall. Urban and rural communities would face drinking water scarcity and further depletion of groundwater reserves. Environmental degradation could trigger alternating cycles of drought and flooding, destabilizing entire ecosystems.

For the Taliban, collaboration with India offers dual benefits political legitimacy and economic gain. By promoting Indian-backed water projects, the Taliban regime seeks to project an image of development at home while drawing strategic dividends abroad. However, this partnership also opens the door for India to use Afghan territory as a pressure valve against Pakistan, weaponizing water under the guise of regional cooperation.

The Salma Dam, inaugurated in 2016 as a “symbol of Afghan-Indian friendship,” remains a stark reminder of how water can be turned into a diplomatic weapon. The project ignited tensions with Iran after diminishing its downstream flow a pattern that may now repeat itself with Pakistan. The message is clear: India’s water diplomacy is not about friendship; it is about leverage.

Recognizing the growing threat, Pakistan has begun exploring the Chitral River Diversion Project, a bold initiative to redirect the Chitral River which contributes more than half of the Kabul River’s volume — into the Swat Basin. This move would reclaim Pakistan’s control over its own waters, enhancing irrigation, boosting hydropower capacity, and insulating the country from future manipulations.

More importantly, it reflects a shift in Pakistan’s water policy from reactive defense to proactive resilience. The country is positioning itself to ensure that no external power can unilaterally dictate its water future.

India’s water ventures in Afghanistan are not merely engineering projects; they are instruments of strategic coercion. Yet, Pakistan’s strength lies in foresight and preparedness. Through scientific planning, regional engagement, and firm diplomatic posture, Pakistan can and must safeguard its hydro-sovereignty.

Water, for Pakistan, is not a matter of diplomacy it is a matter of national security and survival. The state’s response must therefore be clear and unwavering:

Pakistan will protect every drop that sustains its land, its people, and its future.