When gunfire once again echoes through the valleys of South Waziristan, Tank, and Dera Ismail Khan, a disturbing question emerges: are we still living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, or has this region quietly morphed into something far more perilous something unrecognizable under the shadow of escalating militancy? Has Khyber Pakhtunkhwa silently become the new “Khorasan,” the ideological caliphate dreamed of by extremists from Afghanistan to the tribal borderlands?

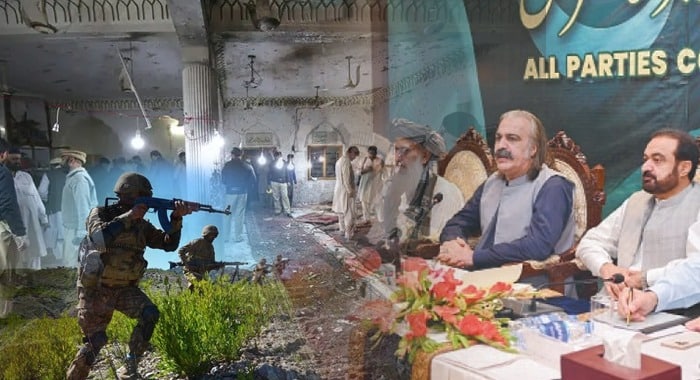

The past several months have seen an alarming resurgence of militant violence across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, particularly in the southern districts. The assassination of tribal elders, targeted killings of police officers, and even attacks on public representatives underscore a grim reality: the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and other proscribed outfits are not only resurfacing they are embedding themselves more deeply than ever. Their growing operational capacity is matched only by the growing absence of the state in these areas.

The districts bordering Afghanistan have become fertile ground for insurgency, fed by a toxic combination of state neglect, crushing poverty, and incoherent policy. This vacuum has allowed both ideological extremism and tactical militancy to flourish, giving way to a wave of violence that is as strategic as it is symbolic.

At the heart of this unfolding crisis is the specter of “Wilayat Khorasan” a geopolitical and ideological project promoted by ISIS-Khorasan (ISIS-K), envisioning a pan-regional Islamic state comprising parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran. While ISIS-K remains primarily active in Afghanistan, its ideological reach now extends into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where it finds willing collaborators or sympathizers among remnants of al-Qaeda, factions of the TTP, and other local militant groups. Though these groups may differ in structure, their shared goal is chillingly singular: to dismantle the state order and establish a system in which constitutional law, democracy, and national sovereignty have no place.

Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has thus become both a corridor and a canvas strategically vital and ideologically contested. Weapons, militants, and narratives flow freely across the Durand Line, eroding Pakistan’s territorial and ideological cohesion. The state, in its current posture, appears increasingly reactive rather than preventive.

Pakistan has in the past claimed significant victories against militancy through operations like Zarb-e-Azb and Radd-ul-Fasaad. Yet, these tactical gains were not translated into lasting peace. The most consequential misstep was the opaque negotiation process with the TTP in 2022, which allowed hundreds of battle-hardened militants to return under the banner of “peacebuilding.” What was hailed as reconciliation has resulted in a renewed bloodbath.

Equally troubling is the squandered promise of the FATA-KP merger an initiative that once offered the hope of political inclusion, legal reform, and economic uplift for the tribal belt. Today, those promises lie in ruins. The newly merged districts still lack basic infrastructure: there are no schools worth the name, no functioning hospitals, and no accessible courts. What exists are checkpoints, security outposts, and the omnipresent barrel of a gun.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking element of this crisis is the systematic silencing of dissent. Journalists who dare to write are pressured into silence. Social activists who speak out often disappear. The tribal elders, once the bridge between the state and the people, are being assassinated one by one. In June 2025 alone, more than 40 security personnel and local leaders were killed in targeted attacks.

Meanwhile, the streets of Tank, Waziristan, and D.I. Khan witness protest marches and rallies almost daily but these cries are met with deafening silence in the national media. The local populace no longer trusts the militants, but neither do they believe in the state’s promises. Both have failed them repeatedly and irreparably.

What makes this moment particularly dangerous is the national indifference. The federal capital seems almost oblivious to the deteriorating situation in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. There is no coherent policy, no political consensus, and no governing vision. The region has once again been relegated to the periphery an expendable frontier in the national imagination.

Institutionally, the situation is dire. The police lack resources, the local governments are inactive, and the judiciary is either absent or ineffectual. Security forces, rather than leading, are now operating in defensive mode. In contrast, the militants have grown more organized, confident, and embedded in the local fabric.

What we are witnessing is not just a security lapse; it is a collapse of political will, institutional capacity, and moral clarity. If Khyber Pakhtunkhwa becomes the new Khorasan, it will not be because the militants succeeded it will be because the state refused to act.

The hour is late, but not irreversible. It demands immediate, coordinated action: a return to institutional governance, a rejection of appeasement, the revitalization of the local justice and education systems, and above all listening to the voices that have long been ignored. The people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa deserve more than checkpoints and condolences. They deserve a state that protects them, represents them, and restores their faith in the republic.