A U.S. federal appeals court has struck down a controversial plea agreement that could have allowed Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-proclaimed architect of the September 11 attacks, to escape the death penalty. The ruling adds another layer of complexity to a case mired in legal ambiguity, political compromise, and decades of delay. The court’s decision comes nearly a year after Mohammed and two co-defendants agreed to a tentative deal with the U.S. government, under which they would plead guilty to charges related to the 9/11 attacks in exchange for life sentences rather than execution. The arrangement, reached behind closed doors, never sat comfortably with all parties involved including victims’ families, many of whom viewed it as a shortcut to avoid public trial and accountability.

Shortly after the agreement surfaced, the U.S. government itself moved to stall the process. In a formal submission, federal prosecutors warned that approving the pre-trial pleas would result in “irreparable harm” to the integrity of the proceedings. A three-judge panel, tasked with reviewing the matter, ultimately voided the deal by a 2-1 vote, stating the case required deeper scrutiny. The court emphasized that the delay should not be construed as a judgment on the guilt or innocence of the accused but the effect was unequivocal: the plea deal is now dead.

Judge Robert Wilkins dissented from the majority, marking yet another division in a case long overshadowed by procedural setbacks and institutional contradictions. Mohammed has been detained at Guantanamo Bay since 2003 and has yet to face a full criminal trial over an attack that killed 2,976 people and reshaped global security paradigms.

Under the now-nullified agreement, families of 9/11 victims were to be granted a rare opportunity to question Mohammed directly, with the accused bound to respond truthfully. The inclusion of this clause was seen by some as an effort to extract information outside the traditional bounds of justice, while others viewed it as a calculated mechanism to bring closure without confrontation.

The very existence of the plea deal became public through a letter from Chief Prosecutor Aaron Rugh, who informed victims’ families that the accused had agreed to admit full responsibility for the attacks in exchange for removal of the death penalty as a sentencing option. However, the exact terms of the agreement were never disclosed, fueling speculation that the deal was more about protecting institutional interests than delivering justice.

Mohammed’s legal team confirmed their client had agreed to plead guilty, but whether that admission was the product of genuine remorse, legal strategy, or years of extrajudicial detention and interrogation remains unresolved.

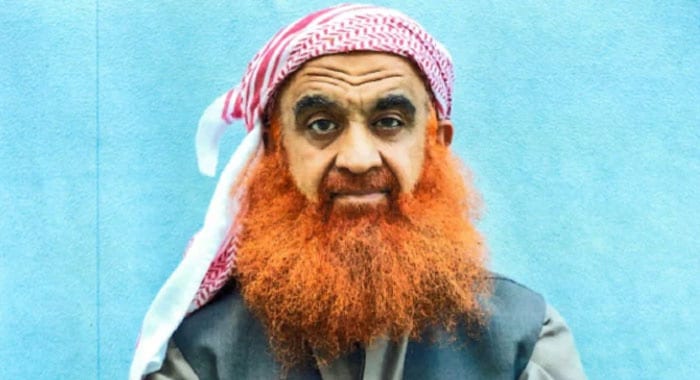

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was born on April 14, 1965, in Kuwait to Pakistani parents. At age 16, he joined the Muslim Brotherhood and later moved to the United States, where he earned a degree in mechanical engineering from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. During his time in the U.S., he became increasingly radicalized, reportedly forging ideological bonds with fellow Arab students.

In 1987, Mohammed is believed to have met Osama bin Laden and joined the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan. His nephew, Ramzi Yousef convicted for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing would become another key figure in the evolving network of transnational militancy.

By the late 1990s, Mohammed had emerged as a key operational planner in al-Qaeda, and his eventual capture in 2003 was touted as a major counterterrorism victory. But years of CIA detention, alleged torture, and shifting legal frameworks have prevented any definitive resolution in court.

While the appeals court decision resets the process, it does little to resolve the fundamental crisis of legitimacy surrounding the prosecution. After more than two decades, the case remains stalled between legal procedure and political paralysis with no clear end in sight.