As Russia becomes the first country to formally recognize the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, a tectonic shift in regional geopolitics is underway. Moscow’s decision has not only revived the Taliban’s diplomatic hopes but also raised questions about who will follow next. Meanwhile, across the border in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), the security situation is deteriorating by the day. While Kabul reaps diplomatic dividends, KP reels from violence, state inertia, and a conspicuous absence of political leadership.

For over a week now, KP has been gripped by a fresh wave of militancy. On a single day, security forces claimed the killing of 30 militants. Yet the streets of Bajaur mourned a civil servant, Assistant Commissioner, gunned down in a targeted attack. These aren’t isolated incidents they represent a pattern, a return to the dark days when bombs and burials marked the rhythm of life in the tribal belt. But this time, the story carries a cruel irony: while the Taliban consolidate power with international backing, the Pakistani state is struggling to maintain order within its borders.

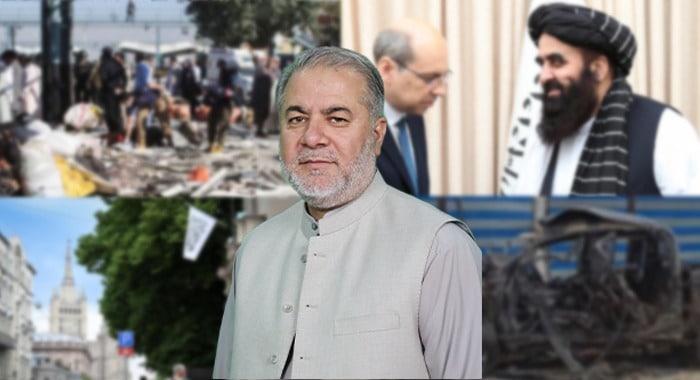

The roots of this paradox run deep. Since the Taliban’s return to power in August 2021, under Amir Khan Muttaqi’s diplomatic stewardship, Afghanistan has systematically pursued international legitimacy. The Taliban have assured foreign governments that Afghan soil will not be used for terrorism, and in return, they’ve pushed for recognition and investment. Russia has now reciprocated, becoming the first to legitimize their rule since the 1990s, when only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE extended such recognition. Now, with China, Turkey, Qatar, and the UAE deepening engagement, it’s only a matter of time before others follow.

But what does this mean for Pakistan especially KP?

Pakistan’s own Taliban problem the TTP continues to fester. A majority of its leadership and fighters remain sheltered in Afghanistan. Since military operations drove them out of KP, many have simply regrouped across the Durand Line. As pressure mounts in Afghanistan, they seep back into southern KP districts: North and South Waziristan, Bannu, Lakki Marwat and alarmingly, even Karak, once untouched by militancy. In recent weeks, Taliban fighters from the Khattak tribe have emerged, shattering long-held assumptions that some areas and ethnic groups were immune.

The TTP under Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud has recalibrated. Unlike its previous brutal chapter under Fazlullah, marked by school massacres and market bombings, the group now prioritizes targeted expansion, political messaging, and selective violence especially in areas where they have resources or local roots. This evolution mirrors the Afghan Taliban’s own shift from insurgents to rulers. The TTP, too, is seeking to win “hearts and minds,” and they seem to be learning fast.

What remains stagnant, however, is Pakistan’s response particularly from its political leadership in KP. Despite a spike in violence and public anxiety, the provincial government led by Chief Minister Ali Amin Gandapur has failed to assert even symbolic authority. After the killing of the assistant commissioner in Bajaur, no cabinet minister attended his funeral not even Abdul Hakeem, the minister from Swat, the victim’s home district, who showed up days later. In stark contrast, opposition leaders like Ameer Muqam, Aimal Wali Khan, and Mian Iftikhar Hussain traveled great distances to express solidarity. The message could not be clearer: KP’s security crisis has no political ownership.

This absence is not just a moral failing it is a strategic one. Law enforcement cannot function in a vacuum. Security forces must see that elected representatives stand behind them. Without political will, there is no legitimacy, no clarity of purpose, and no cohesive response.

Meanwhile, the specter of another military operation looms large. North Waziristan is once again being discussed as a target for clearance. But times have changed and so has public patience. Thousands of residents have already poured into the streets, staging mass prayers and declaring that they will not abandon their homes this time. These people have already suffered the cost of one war: displacement, destroyed homes, lost livelihoods. They are refusing to suffer again.

Military operations, as currently envisioned, may no longer be the solution. The “bomb-first, evacuate-later” doctrine not only alienates civilians but plays into militant hands. The more homes destroyed, the more resentment festers and the more the state loses the trust of its own people. As seen globally, from Kashmir to Fallujah, counterinsurgency without community engagement often backfires.

Pakistan must learn from history and from the evolving Taliban playbook. The Afghan Taliban have prioritized diplomacy, economic engagement, and regional integration. Their representatives have visited Turkey, China, Qatar, and Central Asia. In Baku, they’ve secured agreements to export Afghan produce through a 15-million-ton capacity port—linking them to Europe, Iran, and Russia. From Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s participation in global summits to quiet diplomacy in the Gulf, the Taliban are no longer just fighters—they are state actors forging economic and political alliances.

In contrast, Pakistan’s strategy is fragmented. While the military undertakes kinetic operations, the political class remains mute. While the Taliban engage Russia, Pakistan juggles crisis after crisis. While Kabul plans trade routes, KP’s districts slide back into lawlessness.

Even India despite historic animosity has maintained quiet engagement with the Taliban. Yet New Delhi remains cautious, wary of Pakistan’s sensitivities. The Taliban too are mindful of the past: they have kept India at a diplomatic distance, recognizing its previous role in destabilizing Pakistan through Afghan soil.

This moment demands not more bombs, but bold rethinking. Security must be intelligence-led, not displacement-driven. The KP government must wake up and lead. Islamabad must recalibrate its Afghan policy with realism, not nostalgia. And above all, the people of KP who have buried too many loved ones and rebuilt too many homes deserve more than another round of senseless war.

Russia has moved forward. Afghanistan is moving forward. Will Pakistan finally stop moving in circles?