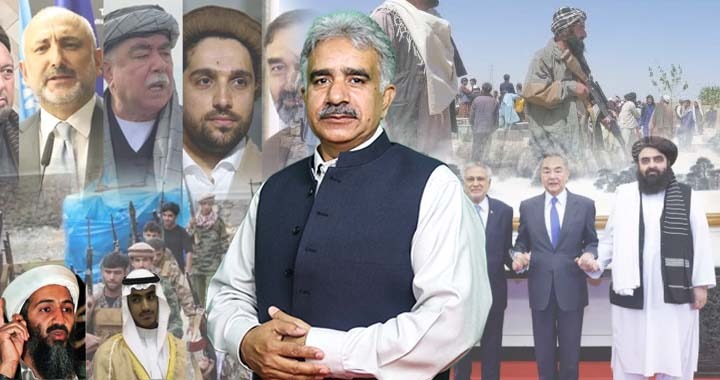

Pakistan’s long standing narrative has been straightforward, that Afghan territory must not be used against any neighbour. The Doha Agreement promised exactly that, yet the current reality has moved sharply in the opposite direction. Afghanistan, instead of becoming a stable state, has drifted into a vast trans-border launchpad for terrorism, a conclusion strongly reinforced by the recent SIGAR report.

According to that report, Al Qaeda maintains control in seventeen Afghan cities. The resurfacing of Hamza bin Laden through a newly released interview, which many believe was recorded inside Afghanistan, only underlines that the group’s senior leadership never left the Afghan sanctuary. Alongside this, between seven and eight thousand TTP militants are entrenched across Paktia, Paktika, Khost, Nuristan, Kunar and adjoining belts. ISIS, meanwhile, remains a looming danger for Central Asia, Russia, and the Hazara Shia population, maintaining an estimated 2,500 fighters.

The SIGAR findings detail an ecosystem of militancy. Nearly seventy Al Qaeda-linked training camps, hosting cadres from TTP, BLA, ETIM, IMU and allied groups, operate without disruption. Uyghur militants under Abdul Haq Turkestani and Imran Turkestani remain active. American military and intelligence assessments echo this picture, identifying Afghanistan as a major global hub for extremist networks.

Two decades of conflict and collapse have left Afghanistan without workable administrative, governmental, economic or rights-protection structures, with no monitoring mechanisms to regulate what is unfolding. The country has taken the form of a black hole. Terrorism, narcotics, illegal trade, human trafficking, nothing remains contained. A new export phenomenon has also emerged, Afghan Taliban fighters travelling to Central Asia, Europe and even the United States, carrying an ideology the current regime wants to spread beyond its borders. Many within the movement now describe Afghanistan as the “state of Khurasan” that must expand towards Jerusalem and Israel.

A Regional Web, China’s Stakes, and the Approaching Edges of Instability

China’s interest in stabilising Pakistan Afghanistan ties is driven not by sentiment but by massive strategic investment. The Belt and Road Initiative, CPEC, the rail line from Kashgar through Torkham and Chaman into the Central Asian corridor, mining projects, and the trilateral train project involving Pakistan, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan all tie Beijing’s economic future to the region’s peace. China cannot afford turbulence that threatens these routes or invites external forces into Afghanistan, including the United States returning in the form of a UN peacekeeping deployment at Bagram, something Beijing views as a major threat.

China also fears the ideological spillover into Xinjiang, particularly from groups like the Turkestan Islamic Party and ETIM. Any vacuum in Afghanistan invites external agencies, especially India, to support militant groups hostile to Pakistan, Iran and China. This pushes Beijing to encourage dialogue, but the central question remains whether the Afghan Taliban take any of these diplomatic overtures seriously. Qatar, Turkey and Saudi Arabia have all failed to secure compliance. Behind the Taliban, there may be support structures involving Middle Eastern states, Israel, India and the United States. Former Afghan vice president Amrullah Saleh recently claimed that 450 million dollars arrive monthly into Taliban hands, a fresh tranche delivered through a chartered plane. This money is not building schools or developing infrastructure, it is fuelling militant networks, backed by an arsenal of US origin equipment, from aircraft to Humvees, night vision gear, surveillance systems and advanced weapons.

A deliberate construction seems underway, a regional factory of fighters, weapons and ideology designed for export, a threat to every neighbour. China views this as an intolerable risk.

Simultaneously, resistance within Afghanistan is rising. Recent NRF attacks in Panjshir killed more than seventeen Taliban fighters through coordinated IED and ambush strikes. Other strikes in Badakhshan claimed additional Taliban casualties. These are not isolated incidents but signs of an organised resistance under figures like Ahmad Massoud and General Muin. Should Tajik, Hazara and Uzbek communities mobilise in the north, as grievances grow over the regime’s refusal to grant rights, the Taliban, already overstretched, would confront internal battles on three fronts, eastern belts, central Afghanistan, and the northern periphery. Such developments could trigger the beginning of the regime’s collapse.

The refugee question compounds this instability. Pakistan and the United States have pushed Germany to tighten screening of Afghan migrants after reports linking many arrivals to crimes, trafficking, sexual offences and suspected terror activity. The hasty evacuation under the Biden administration brought thousands without verification, some later linked to violent crimes in Washington and Europe. Many refugees had backgrounds in combat, intelligence gathering, or working as informants during the US occupation. Western governments now question how individuals disloyal to their own homeland can be loyal to their host states.

Pakistan hosts 2.82 million Afghan refugees, only 1.2 million legally registered. Camps have been dismantled and facilities withdrawn as the government moves to repatriate four to five hundred thousand individuals. UNHCR holds more than 115,000 Afghan asylum requests. The international climate has shifted, with asylum severely restricted across Europe and the US. Pakistan insists that undocumented residents cannot remain, especially when 60 to 70 percent of recent terror attacks involve Afghan nationals. A long term mechanism for visas or citizenship must be formalised, but political rhetoric cannot justify keeping hundreds of thousands of unregistered individuals indefinitely.

The KP government faces additional pressures. Tensions between provincial and federal administrations, escalating attacks in border districts, and a revival of militancy have pushed KP to strengthen the CTD. A new counter terrorism force has been formed, 650 investigators upgraded, twenty one CTD units reactivated and 7.7 billion rupees allocated for restructuring. KP supports deportations ordered by the federal ministry, arguing that undocumented residency fuels law and order breakdowns. Without proper visas, Pakistan cannot allow unchecked inflows.

Iran’s model shows strict separation between nationals and non nationals. Pakistan has been generous, with refugees living freely in cities, houses and hotels, evolving into economic migrants. With the Taliban claiming stability and prosperity at home, their citizens must return and contribute to reconstruction. If Afghanistan is peaceful, why are so many unwilling to go back The burden cannot remain on Pakistan alone.

The world has begun recognising that Afghanistan’s instability is a root cause for global security threats. With the Taliban regime exporting fighters, enabling networks and refusing to meet commitments, a major shift appears inevitable. If this trajectory continues, a dramatic internal change or even the fall of the Taliban regime may not be far.