( Shamim Shahid )

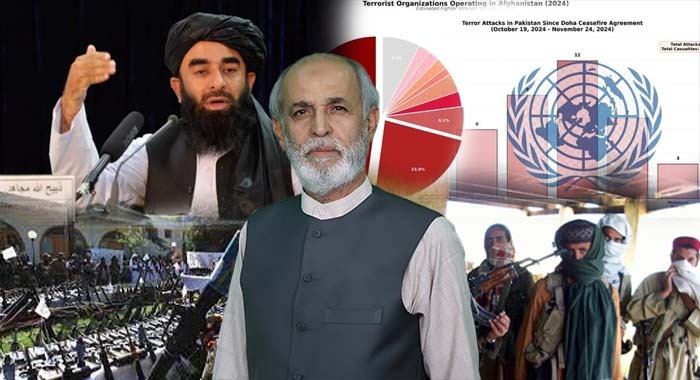

Pakistan is once again at the crossroads of a significant security challenge, as attacks in Hangu, Bannu, Peshawar, and other parts of the country underscore a persistent and growing threat from militant groups, particularly the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and affiliated Afghan Taliban networks. Recent incidents have laid bare the complex, transnational nature of terrorism in the region and have raised pressing questions about Pakistan’s preparedness, its relations with neighboring Afghanistan, and the broader implications for regional stability.

The spate of attacks targeting police check posts in Hangu and Bannu has once again highlighted the operational capabilities of the TTP. These attacks are not isolated incidents but part of a wider pattern of militancy across Pakistan’s northwestern belt and beyond. Attempts to target high-security installations in Islamabad near Kachari and at the Peshawar Frontier Corps headquarters, although unsuccessful, further emphasize the audacity and reach of these groups. Meanwhile, areas in North Waziristan, Bajaur, and Teera continue to witness frequent terrorist activities, reflecting the enduring presence and organizational sophistication of militant networks.

Concurrently, recent statements from the spokesperson of the Afghan Taliban, Zabihullah Mujahid, alleging drone strikes carried out by Pakistan in Paktika, Khos, and Kunar, have added a new layer of complexity to the security calculus. These accusations are coupled with explicit threats of retaliatory operations, signaling potential escalation that is cause for serious concern in Islamabad. Social media is rife with videos suggesting that Afghan Taliban elements are actively facilitating TTP operatives in crossing the border, raising alarm about the porousness of Pakistan-Afghanistan border security and the potential for coordinated cross-border attacks.

From the perspective of Pakistan’s internal security, the Taliban and the TTP are essentially two sides of the same coin. While often portrayed as separate entities, both groups share objectives, resources, and operational networks. The resurgence of Taliban influence in Afghanistan has provided a space for the TTP to regroup and strengthen, particularly for cadres who remained unemployed or marginalized following the Taliban’s takeover in Kabul. Over the last 15 to 25 years, these operatives have engaged in sustained terrorist activities as a means of survival, forging alliances not only with the TTP but also with other militant outfits such as Daesh. This cooperation ensures that past patterns of militancy are likely to continue, posing persistent threats to Pakistan’s internal security.

Border security between Pakistan and Afghanistan has improved over time, with check posts, fencing, and surveillance reducing the likelihood of large-scale infiltrations by ordinary operatives. Nevertheless, where facilitators exist either within Pakistani territory or across the border these groups can exploit gaps to move personnel, weapons, and resources. It is therefore critical to understand that incidents of terrorism inside Pakistan are frequently carried out by small, compartmentalized groups affiliated with the TTP. Each subgroup may operate under a different name but ultimately remains part of the broader TTP network. This decentralization allows the organization to maintain operational continuity while minimizing the risk of full-scale exposure or disruption.

Despite the significant number of counter-terrorism operations conducted in Pakistan estimates suggest thousands of raids in the past year alone—the problem persists. The resilience of militant networks is rooted in their widespread support base, comprising facilitators and sympathizers not only in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa but also across Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, Azad Kashmir, and Gilgit. The organizational reach of these networks illustrates that terrorism in Pakistan is not confined to traditional hotspots but is instead a nationwide challenge. The historical evolution of these networks is telling: from 2005 to 2014, militants in North Waziristan operated under labels such as the Punjabi Taliban, and many were not proficient in Pashto, indicating their diverse ethnic composition and mobility. Post-2014, displaced militants moved into Afghanistan, seeking new bases of operation, while others remained in Pakistan under the cover of local communities and tribal networks. Identifying and neutralizing these actors remains a critical task for the Pakistani state.

The deterioration of Pakistan-Afghanistan relations compounds the security challenge. In recent developments, Afghanistan’s government prohibited the use of its airspace by Pakistan, affecting commercial aviation and raising logistical and economic concerns. Flights from Peshawar that previously traversed Afghan airspace now face longer routes, increased costs, and operational complexities. Beyond aviation, border closures following recent escalations have significantly disrupted trade and supplies, resulting in shortages and rising prices in Afghan markets for essential commodities such as rice, ghee, and cement. This has broader implications for regional stability and underscores the intertwined nature of security, economic, and humanitarian considerations.

Within Pakistan, the operational threat posed by the TTP and affiliated militants is multifaceted. Small groups exploit opportunities wherever and whenever they arise, often engaging in attacks days, weeks, or months apart. This opportunistic approach, coupled with facilitators on both sides of the border, ensures that the threat remains persistent. The recent statement by Zabihullah Mujahid threatening retaliatory attacks is emblematic of the risks posed by these groups, particularly given historical precedents where such threats have been followed by deadly assaults affecting civilians, including women and children. While the Afghan Taliban’s capacity for large-scale operations is limited due to a lack of air power, modern weaponry, and technological resources their ground networks and TTP affiliates still pose a serious security concern for Pakistan.

It is essential to recognize that the Taliban’s political authority in Afghanistan is fragile. They assumed power not through widespread popular support but under the framework of the Doha Agreement. Many Afghans remain opposed to their policies, creating internal tension that intersects with their external posturing toward Pakistan. While the Taliban’s lack of modern military capabilities limits their direct threat, their facilitation of TTP operations, combined with historical expertise in guerilla tactics, enables them to exert indirect pressure on Pakistan.

Historically, the security of Pakistan’s western border relied heavily on tribal cooperation. Prior to 2015, tribesmen effectively acted as de facto border guards, ensuring stability without formal salaries or heavy militarization. However, deteriorating governance, alienation of tribal leaders, and the resurgence of militant networks have weakened these traditional safeguards. Revitalizing trust and cooperation with tribal communities is crucial for sustainable border security. This approach, emphasizing local collaboration alongside formal military measures, could reduce the need for extensive force deployments while fostering stability and resilience.

The broader geopolitical dimension cannot be ignored. Pakistan’s security strategy is influenced by regional and international actors. While the United Nations, European countries, and some Asian allies have expressed support, the United States’ role often complicates matters, as its policy decisions are driven primarily by its own interests. Pakistan must navigate these dynamics carefully, balancing international engagement with the imperative of securing its territory and people. The lessons of history are instructive: external interventions or pressures that fail to align with Pakistan’s strategic interests have often exacerbated domestic security challenges.

The internal security situation is further complicated by the decentralized nature of TTP operations and their ability to maintain networks across multiple provinces. Even when large-scale operations succeed in neutralizing specific elements, new cells emerge, often operating under different banners but maintaining continuity with the original organization. This adaptability underscores the importance of intelligence-led counter-terrorism strategies, interagency coordination, and long-term engagement with local communities to disrupt the recruitment, facilitation, and logistical networks that sustain militancy.

Pakistan’s response to these challenges must therefore be multi-pronged. Military operations remain necessary but are insufficient on their own. Diplomacy, both bilateral with Afghanistan and multilateral with regional partners, is essential to mitigate cross-border threats and maintain trade and communication links. Simultaneously, economic and social development in border areas can strengthen resilience against extremist influence, while systematic engagement with tribal leaders and local governance structures can restore trust and cooperation. Only through a comprehensive approach, integrating security, political, and socio-economic measures, can Pakistan hope to address the root causes of terrorism and prevent the re-emergence of destabilizing networks.

In conclusion, Pakistan’s security concerns are both immediate and structural. Attacks in Hangu, Bannu, Peshawar, and North Waziristan, coupled with threats from Afghan Taliban networks, underscore the persistent challenges posed by militant groups. The TTP, while often fragmented into subgroups, retains operational capacity, local support, and the ability to exploit regional dynamics. Addressing this threat requires a nuanced strategy that combines military vigilance, intelligence operations, diplomatic engagement, and local cooperation. Historical lessons remind us that the stability of Pakistan’s western border has always relied on a combination of state capability and community trust. Revitalizing these mechanisms, alongside a clear understanding of regional geopolitics, will be essential to safeguard Pakistan’s security in the years ahead.

The current situation presents both a challenge and an opportunity for Pakistan: a challenge to manage immediate threats while navigating deteriorating relations with Afghanistan, and an opportunity to strengthen internal resilience, reaffirm regional partnerships, and demonstrate the strategic maturity of a civilised state in addressing complex security issues. By combining tactical operations with long-term policy measures, Pakistan can not only neutralize present threats but also lay the foundation for enduring stability along its western frontier.