Strained relations between Pakistan and the Kabul’s interim Taliban administration are no longer episodic disruptions, they have settled into a pattern of structured tension. What we are witnessing today is not a temporary diplomatic chill but a conditional relationship, one in which both sides remain locked into positions they consider non-negotiable.

Pakistan’s foremost demand is security-centric: curbing cross-border attacks and dismantling militant safe havens operating from Afghan soil. Kabul, on the other hand, frames its core position around sovereignty and mobility, insisting that border regimes must remain open and that pressure tactics from Islamabad must recede in favor of engagement based on what it calls parity and mutual respect.

This dual rigidity has produced a diplomatic stalemate. Neither side appears willing to concede ground, and without movement on core security concerns, dialogue risks becoming procedural rather than productive.

The atmosphere within Afghan policy circles reflects this hardening posture. Conversations with Afghan journalists and observers suggest that the Taliban leadership views external pressure, particularly from Pakistan, through a lens of historical grievance and ideological assertion. The metaphor relayed to me recently, that Kabul does not want assistance “in a bowl but in a strainer,” captures this psychology: an insistence on dignity framed through resistance, even if materially costly.

Yet the costs are not abstract.

They are visible across trade corridors and border economies. Since the disruption of bilateral trade flows, entire economic chains linked to Afghan transit have felt the shock. Pakistani transporters, drivers, customs handlers, and labor networks tied to cross-border commerce have faced mounting losses. Agricultural producers in Punjab, particularly those dealing in perishable goods such as bananas, guavas, and potatoes, have seen export channels constrict.

Small and medium industries, plastics, crockery, packaging, and associated manufacturing sectors, have also absorbed the fallout. Reports of hundreds of stranded cargo containers at crossing points illustrate how political deadlock quickly transforms into economic paralysis.

This interdependence makes the stalemate mutually damaging. Afghanistan faces its own fiscal and humanitarian crises, but Pakistan too is paying a steep commercial and security price.

If both sides remain entrenched, the deadlock will persist. Historical precedent shows that border tensions between the two countries are not new. Clashes, closures, and diplomatic stand-offs have surfaced repeatedly across decades. But the present phase carries an additional layer of complexity, one rooted in militancy.

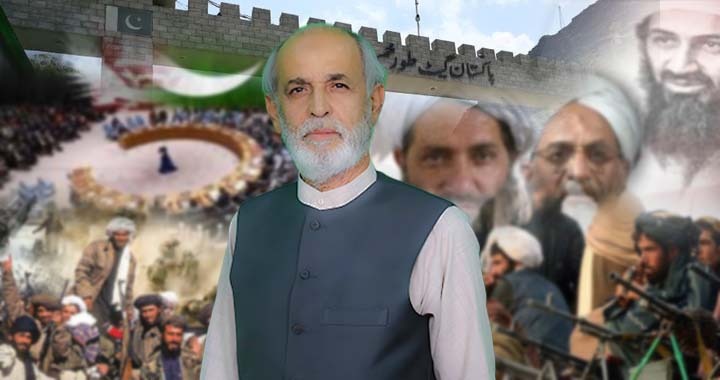

Recent UN reporting on the presence of Al-Qaeda leadership in Kabul has generated international attention, but from a regional security standpoint, this revelation is neither shocking nor new. Militant relocation into Afghanistan accelerated the moment Kabul fell on 15 August 2021. That was the inflection point when multiple transnational and regional groups found ideological space and operational breathing room.

The killing of Ayman al-Zawahiri in a Kabul airstrike in 2022 was itself a defining indicator. It demonstrated not only presence but confidence of sanctuary. The fact that the incident remains insufficiently probed, despite earlier Taliban assurances, continues to raise credibility questions internationally.

More importantly, the security landscape extends far beyond a single organization.

The militant ecosystem inside Afghanistan today is layered. Alongside Al-Qaeda, groups such as ISKP, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, the Turkistan Islamic Movement, and regionally aligned insurgent factions operate in varying degrees of visibility and mobility. Their coexistence creates an enabling environment, whether through passive tolerance, logistical overlap, or ideological alignment.

For Pakistan, this convergence translates directly into internal instability. Violence in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, insurgent activity in Balochistan, and the persistence of TTP attacks form part of the same security continuum. When cross-border sanctuaries remain intact, domestic counter-terror gains become harder to consolidate.

These pressures intersect with Pakistan’s own political and economic strains. Rising militancy, political polarization, and federal tensions collectively shape the investment climate. No external investor or trade partner views such an environment as stable ground for long-term engagement.

This is why de-escalation is not merely diplomatic preference but economic necessity.

Both Pakistan and Afghanistan stand to benefit from recalibrating their approach. However, given Pakistan’s institutional capacity and regional leverage, proactive initiative from Islamabad could carry greater stabilizing weight. Confidence-building measures, calibrated engagement, and structured security dialogue may offer pathways out of the present impasse.

The alternative, sustained hostility layered over militant sanctuary realities, risks deepening instability for both neighbors.

For two Muslim countries bound by geography, trade, and history, prolonging this deadlock serves neither security nor prosperity. Progress will depend not on rhetorical parity but on tangible movement, particularly on the question that sits at the heart of the crisis: militancy operating from Afghan soil and its spillover consequences for Pakistan.

Until that core issue is addressed with clarity and seriousness, every diplomatic contact, ambassadorial meeting, or multilateral reassurance will struggle to move beyond symbolism.