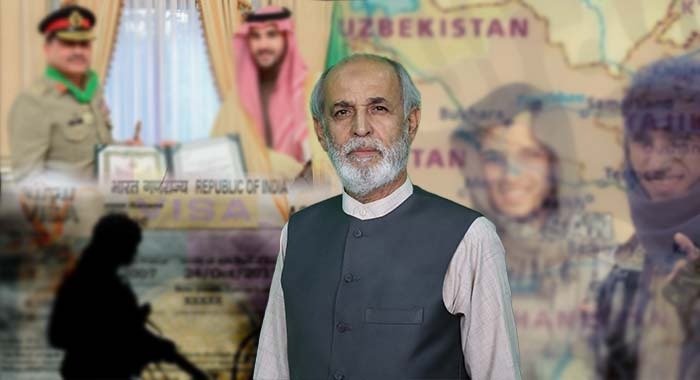

(Shamim Shahid)

A troubling report has surfaced that demands serious reflection from policymakers, analysts, and the international community alike. According to this report, India is considering or has initiated a policy of granting visas to individuals affiliated with various militant and extremist organisations operating in Afghanistan. If this assessment is even partially accurate, it represents not merely a controversial diplomatic move but a dangerous contradiction to the global consensus on counterterrorism. At a time when the world claims to be united against extremism, such steps risk undermining years of collective effort and destabilising an already fragile region.

The immediate concern is not confined to Pakistan alone, although Pakistan will undoubtedly be among the most affected. This is a regional issue with far-reaching implications for South Asia, Central Asia, and beyond. Countries such as Canada, Germany, Australia, Bangladesh, and Pakistan have already expressed concerns over the broader patterns of selective counterterrorism and inconsistent policies being pursued by certain states. These apprehensions are not born out of rivalry or rhetoric but from lived experience with the devastating consequences of militancy.

On one hand, the international community repeatedly asserts that terrorism must be confronted in all its forms, without distinction or political convenience. On the other, we see policies that appear to differentiate between “good” and “bad” militants, depending on immediate strategic interests. This double standard is precisely what has prolonged conflicts in Afghanistan and its surrounding regions for decades. If militant actors are legitimised through visas, medical treatment, shelter, or logistical facilitation, it sends a clear signal that violence can be rewarded under the guise of diplomacy.

Reports suggesting that injured militants receive shelter and medical facilities across borders are especially alarming. Providing humanitarian treatment to civilians is one thing; extending systematic support to armed extremists is quite another. Such actions not only violate the spirit of international counterterrorism commitments but also embolden networks that thrive on chaos. Militancy does not remain confined to borders. History has repeatedly shown that groups nurtured for short-term strategic gains eventually outgrow their patrons and turn into uncontrollable threats.

Afghanistan today stands at a critical crossroads. The Taliban’s return to power has not brought stability or clarity. Instead, it has deepened uncertainty, both within the country and across the region. Despite repeated assertions, the Taliban leadership has yet to present a coherent political or economic roadmap. Governance appears reactive rather than visionary, driven more by ideological rigidity than by the needs of a war-weary population. In this vacuum, extremist elements find space to regroup, reorganise, and expand.

The question, then, is how the world should engage with the Taliban and the broader Afghan reality. Negotiations, in principle, are not objectionable. Dialogue has often been necessary in complex conflicts. However, negotiations without pressure are ineffective, and pressure without a political strategy is counterproductive. What is required is a calibrated approach that combines engagement with firm economic, diplomatic, and social leverage.

Countries such as Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates possess significant influence over segments of the Afghan leadership. This influence is not merely diplomatic; it is deeply economic. Many Taliban figures and their families have investments, residences, and financial interests in these countries. This reality provides the international community with non-military tools that are far more effective than repeated kinetic operations. If economic activities are restricted, if financial networks are scrutinised, and if privileges enjoyed abroad are conditioned on behavioural change, pressure will be felt where it matters most.

Military operations alone have proven insufficient for more than two decades. From 2003 onwards, operations have been conducted across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the former tribal districts with enormous human and material costs. While such operations may temporarily disrupt militant activity, they do not address the underlying dynamics. After every operation, militant groups splinter, regroup, and often re-emerge in greater numbers. Force, when detached from political reconciliation and community trust-building, becomes a revolving door rather than a solution.

One of the most overlooked elements in counterterrorism strategy is the role of local populations. No operation can succeed without the trust and cooperation of the people who live in affected areas. These communities are often the first victims of terrorism and the last beneficiaries of state protection. Expecting them to stand up to well-armed militants without adequate resources is unrealistic and unjust. If the state demands sacrifices, it must also fulfil its responsibilities by providing security, compensation, and long-term development.

Compensation policies, in particular, reveal a troubling disconnect. Offering a few hundred thousand rupees for homes destroyed in conflict zones is not merely inadequate; it is insulting. Rebuilding a house today costs several times more than what is typically offered. Yet, despite this, many local people remain willing to endure hardship for the sake of peace. What they demand in return is not charity but justice, security, and dignity.

Another deeply concerning development is the treatment of Afghan refugees. Decades of conflict forced millions of Afghans to seek refuge in Pakistan, where they lived, worked, and raised families. The recent intensification of pressure on these communities demolishing camps, cutting off utilities, restricting access to healthcare, and cancelling mobile connectivity has created a humanitarian crisis. Collective punishment of refugees does not strengthen security; it breeds resentment and alienation. It also risks creating yet another generation vulnerable to radicalisation.

By alienating Afghan civilians, Pakistan risks turning a displaced population into a long-term adversary, something the region can ill afford. Refugees should not be conflated with militants. Such policies blur moral lines and undermine Pakistan’s longstanding position that its fight is against terrorism, not against ordinary Afghans.

In this broader context, India’s reported visa policy becomes even more problematic. It appears to fit into a pattern where terrorism is condemned rhetorically but accommodated tactically. If true, it raises serious questions about India’s stated commitment to regional stability. Terrorism cannot be fought selectively. The moment states begin instrumentalising militant groups, they erode the very norms they claim to uphold.

The fight against extremism requires consistency, sincerity, and regional cooperation. It demands that no state provide space physical, financial, or political to groups that employ violence for ideological ends. It also requires addressing legitimate grievances through political processes rather than militarisation alone.

Ultimately, peace in this region will not come from visas issued in backrooms, nor from endless military operations, nor from punishing the most vulnerable. It will come from honest engagement, economic accountability, regional consensus, and respect for human dignity. Any deviation from this path, regardless of who undertakes it, threatens not just one country but the entire region.

If the world truly wishes to end terrorism, it must abandon double standards and confront uncomfortable truths. Otherwise, we will continue to chase shadows while the fire of extremism quietly spreads.