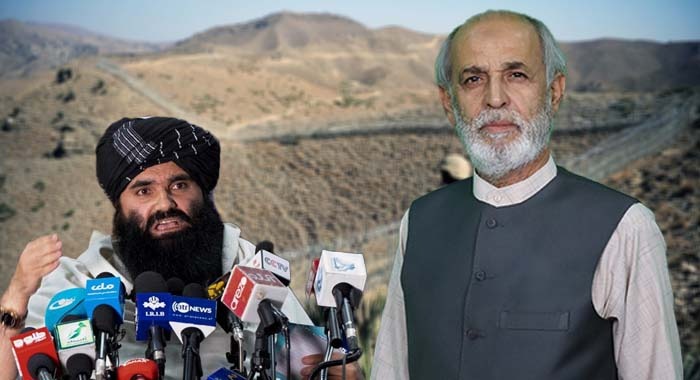

(Shamim Shahid)

Sirajuddin Haqqani’s recent statement from Kabul that Afghanistan seeks peace, dialogue and negotiations rather than war, and that Afghan soil should not be used against neighbouring countries has inevitably triggered intense debate in Pakistan and across the region. Coming from the interior minister of the Taliban government and the most influential leader of the Haqqani network, this declaration cannot be dismissed as a routine diplomatic phrase. Yet, neither can it be accepted at face value. The real question is not what has been said, but why it has been said now and whether it signals a genuine shift in Taliban policy or merely a calibrated political message shaped by internal and regional compulsions.

For Pakistan, the stakes are particularly high. Border terrorism has surged, militant violence has returned with alarming frequency, and trust between Islamabad and Kabul has eroded sharply since August 2021. Against this backdrop, Haqqani’s emphasis on negotiations and non-hostility raises a critical dilemma: does this statement carry any practical guarantees, or is it another episode in Afghanistan’s long tradition of tactical ambiguity?

At first glance, international pressure appears an obvious explanation. However, the reality is more complex. Afghanistan today is not under the kind of sustained, unified international pressure that once forced policy recalibrations. Beyond a few regional and Islamic countries, there is no broad global consensus actively pushing Kabul towards reconciliation with Pakistan. The Western bloc, particularly the United States and its allies, remains largely disengaged or indirectly provocative, viewing Afghanistan more as a pressure point than a partner. China and Russia, while advocating regional stability, have limited leverage over Taliban internal decision-making. In this environment, it is difficult to argue that Haqqani’s statement is purely the product of external coercion.

More telling is the internal context within Afghanistan. This is not Sirajuddin Haqqani’s first public departure from the hardline narrative traditionally associated with the Taliban. Only weeks earlier, he publicly spoke against coercion, argued that no government can succeed by force, and criticised excessive restrictions on Afghan society. These remarks were extraordinary not because they came from a Taliban leader, but because they came from one of the movement’s most powerful figures a man long associated with militancy rather than moderation.

This pattern suggests that Haqqani’s latest message is rooted more in domestic pressures than in foreign demands. Afghan society today is under severe strain. The Institute for Economics and Peace has recently underscored what Afghans already know from daily experience: the country is trapped in a vicious cycle of instability, weak governance, economic collapse and deepening social crisis. Inequality is extreme, state capacity is fragile, and public frustration is rising. The ban on female education and employment has not only crippled the social fabric but has also devastated household economies. Afghanistan’s urban middle class, once a stabilising force, has been effectively dismantled.

What further fuels public resentment is the visible contradiction between Taliban leadership lifestyles and the suffering of ordinary Afghans. Senior Taliban figures have daughters studying in Qatar, Islamabad and other foreign capitals, while millions of Afghan girls are barred from schools at home. This hypocrisy has not gone unnoticed. It has generated a silent but widespread anger one that leaders like Sirajuddin Haqqani cannot entirely ignore.

Relations with Pakistan are inseparable from this internal discontent. Pakistan remains Afghanistan’s most critical economic artery. Trade, transit, employment opportunities and humanitarian access all depend on a functional relationship with Islamabad. Prolonged tension with Pakistan directly translates into higher prices, restricted movement and greater hardship for ordinary Afghans. Haqqani’s statement, therefore, can also be read as an attempt to de-escalate a relationship whose deterioration is politically costly inside Afghanistan.

However, recognising the motivations behind the statement does not automatically validate its substance. Pakistan’s primary concern is not rhetoric but results specifically, the continued presence and operational freedom of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and other militant groups operating from Afghan territory. Despite repeated assurances under the Doha framework and bilateral understandings, cross-border attacks have continued unabated. Ceasefires have been announced, only to collapse quietly. Statements have been issued, only to be contradicted by events on the ground.

It is an open secret that militant networks in the region are deeply interconnected. Afghan Taliban factions, the TTP, and other transnational jihadist groups share ideological affinities, historical ties and logistical channels. While the Taliban leadership may not micromanage every attack, it is implausible to suggest that such operations occur without at least tacit tolerance. The recent shift by the TTP away from openly claiming attacks does not signify disengagement; it reflects a change in tactics, not intent.

In this context, Haqqani’s reference to the Doha agreements deserves careful scrutiny. The Doha process produced multiple understandings one with the United States and others involving regional stakeholders, including Pakistan. Central to these was the commitment that Afghan soil would not be used against any country. Yet, implementation has remained selective and inconsistent. By invoking Doha without outlining concrete enforcement mechanisms, Haqqani has essentially reiterated an old promise rather than offered a new guarantee.

Another critical dimension is the internal power balance within the Taliban. Sirajuddin Haqqani’s influence, while significant, is not absolute. The Kandahar-based leadership, often described as more rigid and ideologically driven, holds decisive authority over strategic direction. Reports suggest that Haqqani has spent extended periods away from Kandahar and operates with limited direct engagement with the movement’s core decision-makers. This raises a fundamental question: does his statement reflect a collective Taliban position, or is it an individual articulation shaped by his own political calculus?

The answer matters immensely. If Kabul and Kandahar do not echo or operationalise Haqqani’s message, it risks becoming another isolated declaration — well-intentioned perhaps, but politically inconsequential. For Pakistan, therefore, the appropriate response is not immediate endorsement or rejection, but calibrated observation. Islamabad must assess not just Kabul’s words, but Kandahar’s actions.

Pakistan’s own experience with negotiations also warrants realism. Recent regional dialogue efforts, including talks in Tehran involving Pakistan, Iran and Turkey, were notable for one glaring absence: the Afghan Taliban. Their refusal to participate highlighted a persistent reluctance to engage in multilateral frameworks that impose accountability. Trusting intermediaries like Qatar, Turkey, China and Russia may be necessary, but it is not sufficient unless Kabul demonstrates seriousness through verifiable steps.

The broader security environment further complicates matters. Afghanistan today hosts a dangerous concentration of militant actors not only Pakistani groups, but also Arab, Central Asian, Turkish and other transnational fighters. Many were imprisoned during the Ashraf Ghani era, only to be released en masse after August 15, 2021. These militants did not disappear; they dispersed, reorganised and embedded themselves across Afghanistan. Their presence is a structural threat, not just to Pakistan, but to regional and global security.

This is precisely why international assessments continue to rank Afghanistan as one of the most unstable countries in the world. Instability is no longer episodic; it is systemic. As long as militant networks remain intact and governance remains exclusionary, no declaration of peace can be more than symbolic.

So how should Haqqani’s statement ultimately be understood? It is, without doubt, a political statement but politics itself is shaped by pressure, fear and necessity. It reflects the anxieties of an Afghan leadership confronting economic collapse, social unrest and diplomatic isolation. It also echoes the unspoken aspirations of ordinary Afghans who do not want perpetual hostility with Pakistan or endless conflict at their borders.

Yet, symbolism cannot substitute for substance. For Pakistan, the benchmark must remain clear and uncompromising: a demonstrable end to cross-border terrorism, dismantling of militant sanctuaries, and credible enforcement of commitments. Without these, dialogue risks becoming a one-sided exercise in patience.

Sirajuddin Haqqani’s message may represent a crack in the Taliban’s monolithic posture and cracks, in politics, can matter. But whether this crack widens into a genuine opening or closes into another missed opportunity depends not on speeches, but on decisions taken in Kabul and Kandahar alike. Until then, cautious scepticism remains not only justified, but necessary.