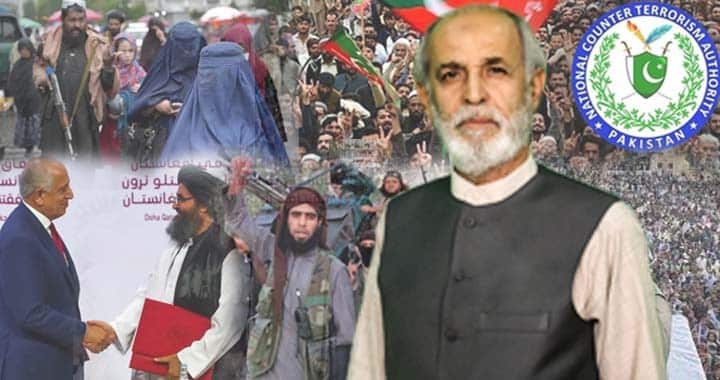

When the second Doha Agreement was signed between the Taliban and the United States, there was cautious optimism that Afghanistan might finally step toward peace after four decades of conflict. The terms of that agreement carried explicit assurances; that Afghanistan’s soil would not be used against any neighboring country, that an inclusive government would be formed representing all ethnic and political groups, and that the rights of Afghan citizens, including women’s education, freedom of expression, and access to health and employment, would be protected.

Yet, within months of regaining power, the Taliban abandoned nearly every commitment they made. Political opponents were arrested, punished, and in many cases, executed. Women were excluded from education and public life. Media and cultural expression were muzzled. Artists, singers, and journalists were silenced. The idea of an “inclusive” Afghanistan collapsed under the weight of authoritarian control and ideological rigidity.

This was not merely a failure of governance, it was the deliberate dismantling of the very principles that could have saved Afghanistan from renewed isolation.

A Network of Militancy, Not Governance

The Taliban leadership’s insistence that Afghanistan’s territory will not be used by militants is contradicted by ground realities. The borders remain porous and multiple extremist groups continue to operate across Afghan territory. Whether it is the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Turkestan Islamic Party (comprising Uyghur militants), or factions linked to Tajik and Kazakh extremists, all remain active to varying degrees inside Afghanistan.

These groups share more than ideology. They share roots. They were trained and indoctrinated on the same land, nurtured by similar networks, and bonded by years of combat under religious pretexts. Expecting the Taliban to disown or disarm these groups is unrealistic because their operational and ideological DNA is intertwined.

The presence of Daesh (IS-KP) further complicates the landscape. Although the Taliban claim to be fighting Daesh, the overlap in recruitment channels and the movement of militants between these factions suggest otherwise. The militant economy in Afghanistan has evolved into a transnational enterprise, one that the Taliban neither control nor can afford to alienate.

Regional Fallout: The Triangle of PTI, PTM and TTP

In Pakistan’s border regions, the consequences of these Afghan dynamics are visible. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has become the epicentre of militant resurgence, with the TTP staging attacks across the province. Parallel to this, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) have both drawn the province’s youth into separate political mobilisations, one parliamentary and populist, the other ethnic and protest-driven.

Instead of uniting young Pashtuns under a constructive democratic vision, these parallel movements have fragmented political energies. PTI’s populism has absorbed urban youth, while PTM’s grievances appeal to those disillusioned by mainstream politics. Meanwhile, the TTP continues to exploit instability and resentment, targeting not only security forces but also political activists, religious figures, and government workers. The outcome is a dangerously divided Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where ideological battles blur the line between activism and extremism.

A World That Watched and Walked Away

It must be said that the international community also bears responsibility. The United States, while negotiating with the Taliban, prioritized withdrawal over peace. The Doha framework was built on American convenience, not Afghan consensus. The Taliban’s return to power was the result of an agreement that lacked safeguards and accountability mechanisms.

Four years later, Afghanistan stands isolated once again. The promises of inclusivity, rights, and reform have turned into tools of repression. Ordinary Afghans yearn not for another foreign-backed regime, but for a stable political order that allows them to live without fear. That will never happen unless the Taliban reorient their foreign policy and internal governance to reflect the needs of the Afghan people rather than the dictates of ideology.

What Pakistan Should Do

Pakistan’s path must be pragmatic, not reactionary. Breaking ties with the Taliban would only deepen hostility and reduce Islamabad’s influence. Instead, Pakistan should continue diplomatic engagement, using both political and religious channels to encourage moderation within the Taliban leadership.

Islamabad must also open dialogue with Afghan civil and political actors, not just the ruling clerics. This includes hosting religious scholars, tribal elders, and opposition figures to create a broad base for peace talks. The two nations share deep cultural and familial bonds; these ties should be used to rebuild trust, not fuel mistrust.

Historically, even during intense conflict; from the eras of Dr. Karmal and Dr. Najibullah, Pakistan and Afghanistan never completely severed their cross-border social and tribal relations. Today, the political gap is wider than ever, but it is not beyond repair. Sustained dialogue, pragmatic diplomacy, and respect for mutual sovereignty are the only viable routes to peace.

The Taliban must realise that governing a country is far more difficult than conquering it. Without change, Afghanistan risks becoming a battlefield for proxy interests once again, a tragedy both Afghans and their neighbours can no longer afford.