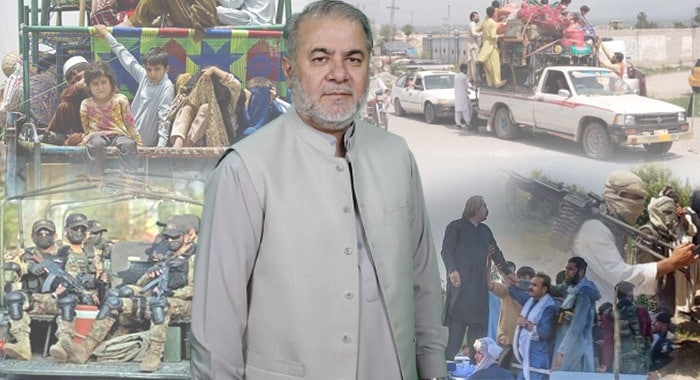

As the security situation in Bajaur tehsil deteriorates and a military operation has commenced in Mamund, we are once again witnessing a familiar pattern: a delayed response to militancy, mass displacement of civilians, and a glaring absence of clear political leadership. The latest advisory directing the relocation of civilians from 33 areas is not just a procedural move, it is a stark reminder of how history continues to repeat itself in Pakistan’s tribal belt.

This is not the first time Bajaur has been at the heart of a security crisis. In 2008, a massive operation forced over half a million people to flee their homes. Many of them have yet to return, rebuild, or even recover. Memories of that time; the bombings, the use of fighter jets, the fear, the trauma, are still raw. And now, in 2025, it appears we are bracing for another cycle of conflict.

What makes this operation different, however, is its context. The threat now is concentrated in the Mamund region, a strategically significant area near the Afghan border. But the history of Mamund’s ties to militancy is long and layered. It was a hub of support for Sufi Muhammad’s TNSM movement in the ’90s. It later became a recruiting ground for militants traveling to Afghanistan. Today, it is reported to house over 1,200 Khawarij, a network resilient enough to threaten pro-state tribal elders, security checkpoints, and the fragile peace of the region.

The recent failure of the jirga, a local tribal jirga (council), to broker a peaceful exit for these terrorists is deeply telling. It underscores the limitations of non-state mechanisms in dealing with ideologically entrenched armed groups. Despite multiple rounds of dialogue, the Khawarij refused to leave. In response, the state issued two ultimatums: either the locals remove the militants themselves, or vacate the area for an impending military operation.

Let us be clear: it is not the people of Mamund who have failed. It is the state that has failed them. Again.

For years, these communities have borne the brunt of militancy and counter-terrorism alike. In almost every major military operation, from Waziristan to Swat, it is not the militants who have suffered the most, but the civilians. The Taliban’s asymmetric warfare tactics allow them to retreat and regroup before the first shots are fired. They abandon homes they do not own, slip into mountains they know well, and vanish into networks they’ve spent decades building. Meanwhile, it is the ordinary people, unarmed, displaced, and forgotten, who pay the price.

And yet, the provincial leadership remains missing in action.

Instead of owning the situation, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s government has only added to the confusion. The Chief Minister’s contradictory statements about whether an operation would occur; first denying it, then endorsing it, reflect not just political immaturity but a serious governance vacuum. When the government speaks in riddles, it only empowers anti-state propaganda and weakens the morale of security forces on the ground.

Military operations are not a matter of pride. They are a last resort. And when necessary, they must be conducted with surgical precision and intelligence, not indiscriminate force. There is some hope that this time, operations may rely more on intelligence and targeted action, with minimal use of heavy artillery. But unless civilian leadership steps up to provide clarity, direction, and rehabilitation plans, even the most precise operation can spiral into chaos.

Moreover, the Khawarij, whether rebranded as Pakistani Taliban or splinter cells, are no longer isolated. Their presence is widespread: Waziristan, Orakzai, Khyber, Mohmand, Malakand, Dera Ismail Khan, Tank, the list goes on. In some places, they’ve embedded themselves through extortion and intimidation. In others, they’ve exploited the absence of development and governance to present themselves as alternatives.

The answer cannot lie solely in the barrel of a gun. Long-term peace in Bajaur and across KP depends on strengthening local institutions, building trust with communities, and empowering police and paramilitary forces who understand the language, the culture, and the terrain.

The people of Bajaur; educated, peace-loving, and patriotic, deserve better. They don’t want to be the battleground in a war that has already robbed them of years of progress. They want peace, schools, hospitals, roads, not drones and checkpoints. They want a future where the government stands with them, not behind press releases.

August 14 is a day of celebration. But this year, it carries the shadow of a planned terror attack, which security sources have thankfully thwarted in advance. That terrorists continue to exploit national days for maximum psychological impact shows their evolving tactics. It also shows how fragile our internal security still is.

The lesson is clear: without strong political will, without clear ownership from both provincial and federal governments, and without a firm, unified stance against militancy, the cycle will continue. Displacement. Operation. Withdrawal. Regrouping. Repeat.

It is time for the government to break the cycle; not with slogans, but with sustained, courageous governance. The people have done their part. Now, the state must do the same.