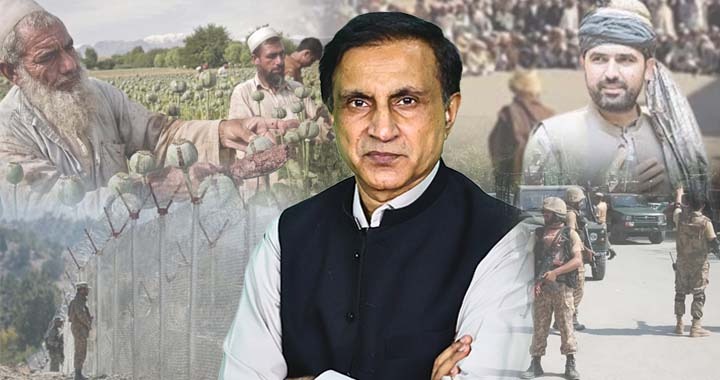

When Ali Amin Gandapur was in power, we were told we wanted to negotiate for peace. Even then, the authorities said, “you can try.” I remember inviting jirgas from Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, North and South Waziristan, and Orakzai, almost all of our merged areas. We sat with them and talked in great detail, for hours. But when I asked Ali Amin Gandapur the purpose of these jirgas, he said that after the local jirgas we would hold a grand, joint jirga of all tribes. I asked what that jirga would do, and he offered two options: one, we would talk directly to local terrorist commanders, and two, while negotiating with the Afghan government, the provincial government would engage with Kabul and we would even convene a Loya Jirga.

It was a big exercise, yet the result was zero. Gandapur’s government went home, the jirga work was left unfinished, and despite the large turnout; fifty, seventy people from different areas arriving at the chief minister’s house in Peshawar for hours of negotiations, nothing came of it. The same pattern has returned with the new chief minister, Sohail Afridi. The issue with some parties, notably PTI, is that they want the provincial administration to talk to the banned TTP, to halt operations and resume negotiations.

There are two basic points here. First, if you want to talk to Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, you must talk to their elders. What will local commanders or small groups negotiate about? I recall an operation planned in Bajaur, followed by a small scale action. The next day tribal elders requested a chance to negotiate, and they were welcomed. An 80-member jirga was formed, but when they reached the Taliban positions they were told to send only eight or ten negotiators. There were seven rounds of talks, and in one round even the Ulema took part, hoping these were their students and acquaintances. Everyone wants peace, but method matters. Seven out of seven rounds failed, the terrorists refused to agree. In Tirah the elders were given a chance too, yet the demands that came up were stark: let us establish an Islamic system in FATA and the merged areas, give us freedom to do as we please. You cannot allow a state within a state.

I lay out these scenarios so readers understand how many efforts have been tried before. Now Sohail Afridi proposes an Aman Jirga that is somewhat different because political parties will be invited, all provincial political leadership will be part of it, and former chief ministers and governors will be consulted about past efforts. The provincial assembly has been prepared for a jirga on November 12 to agree a common line. We will have to see which parties attend and what strategy they adopt. A simple truth is this: if you want peace, you must also define the method to achieve it. How will we bring peace?

Even if you agree to negotiate, practical limits remain. How will a provincial government negotiate with the banned TTP when it is the federal government’s responsibility? The terrorists are not even inside Pakistan in significant numbers, they are based in Afghanistan. Pakistan’s leadership at the highest level, including Shahbaz Sharif and the Field Marshal Asim Munir, have publicly rejected negotiating with the banned TTP, given their record of killing soldiers and civilians. Their barbarism makes talks untenable now. So I find it hard to understand what the provincial government expects to achieve with another round of exercises.

Recent evidence has made the situation clearer. Audio and other material have surfaced suggesting senior Afghan Taliban commanders direct local commanders to help banned TTP fighters cross the border. Pakistan has placed identification cards, documents and videos before Kabul and the international community. At this point denial is difficult. Negotiations are sometimes used to buy time, to push a narrative that you want peace and reject fighting. But when the other side treats talks lightly and offers excuses, doubts grow that they are serious.

If the Afghan Taliban truly speak of Islam and sharia, why are they involved in terrorism in a Muslim country like Pakistan? History explains part of this contradiction. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the world rallied and Pakistan became the base for the mujaheddin. Afghans and Pakistani fighters fought and trained side by side for decades, shared shelter and bonds, and formed relationships stronger than friendship. Given that shared history, it is unrealistic to expect the Afghan Taliban to suddenly act decisively against groups with whom they were forged in conflict.

That said, intention matters as much as capacity. If Kabul’s intention is genuine, capacity can be built. The claim that TTP fighters are highly trained and that confronting them would collapse the Afghan government is frequently heard. They argue they cannot remove or control them. If the Afghan authorities show commitment, and if Pakistan and others back them, capability can be developed. Pakistan has a large, well-equipped army; still, we conduct thousands of operations, and our soldiers and police continue to be martyred. These are not bands of forty or a hundred, they are in the thousands. For this reason the Istanbul negotiations are important.

From previous rounds, including Doha where only a ceasefire was agreed, and the first phase in Istanbul which nearly ended without agreement, a joint mechanism was proposed to investigate cross-border incidents and hold culprits accountable. That mechanism, however, faces enormous practical challenges. The Pakistan-Afghanistan border runs some 2,600 kilometres across mountainous and inaccessible terrain, where fencing and continuous deployment are unrealistic. Terrorists use those difficult areas because they know forces are limited there. We cannot place five and a half lakh troops everywhere, and even a fence cannot stop human, drug and weapons smuggling entirely.

Until there is sincerity between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and until both sides share clear intentions and a joint commitment to end misuse of border sanctuaries, it will be hard to curb extremism and militancy. In Tirah and surrounding areas, drug cultivation, notably poppy and cannabis, is the livelihood of perhaps 85 percent of families there. Smugglers and mafias profit massively, with one acre worth tens of lakhs at harvest. Terrorists take a share, as do local power brokers and criminals, funding further violence. Unless the federal government, provincial authorities, local communities and security forces come together with an economic alternative, arrests alone will not solve the problem.

To be effective there must be four stakeholders on the same page: the local people, the provincial government, the federal government and our forces. The army can do its job, but the federal government must offer an economic package to those who depend on illicit crops. In the past, promises of industrial estates and incentives were made to persuade people to abandon poppy cultivation, but projects were left incomplete and investors pulled out. The result was abandonment and disillusionment. Any eradication drive must be paired with viable livelihood alternatives, employment opportunities, education and healthcare, otherwise resistance will be inevitable.

The narcotics menace is not a local issue, it is global. The rise in methamphetamine use, the spread of “ice” among youth in colleges, and the international smuggling networks all demand serious, sustained action. If we are to dismantle financing streams that fuel terrorism, we must treat drug suppression as part of a comprehensive counter-terrorism plan, linked to development and law enforcement.

So where does that leave us regarding the current negotiations? I do not see any imminent solid breakthrough. It is possible to keep the talks going, to keep channels open while insisting on full and verifiable actions. Talking without a complete, enforceable solution is meaningless. The core questions remain: where will thousands of fighters settle, who will detain or hand them over, and how will responsibilities be shared? These are Pakistan’s demands, and they are realistic. We should maintain hope, but not expect a sudden resolution.