(Shamim Shahid)

Afghanistan once again finds itself at the centre of a complex regional equation where security, diplomacy and internal political contradictions intersect. The recent deadly explosion in Kabul, which claimed eight lives including those of two Chinese nationals, is not merely another tragic incident in a country accustomed to violence; it is a stark reminder that Afghanistan’s unresolved security crisis continues to carry serious regional and international consequences. This single attack has the potential to reshape China’s engagement with Afghanistan, deepen Pakistan’s strategic anxieties, and further expose the Taliban government’s internal divisions at a time when the country can least afford isolation.

China’s relationship with Afghanistan since the Taliban’s return to power has been driven less by ideology and more by pragmatism. Beijing does not seek to transform Afghanistan politically; its core interests are stability, security for its citizens, and protection of its economic investments. The killing of Chinese nationals in Kabul directly challenges these priorities. China has consistently shown that while it is willing to engage with unstable environments, it draws a firm line when the safety of its citizens is compromised. From Pakistan to parts of Africa, Chinese policy has demonstrated a pattern: economic engagement continues only as long as host governments can guarantee a minimum threshold of security.

The Kabul blast therefore places the Taliban in a difficult position. On one hand, China remains one of the few major powers willing to maintain diplomatic engagement and explore economic cooperation with Afghanistan despite the absence of international recognition. On the other hand, Beijing will not hesitate to scale back investment, restrict movement of its personnel, or even rethink its Afghanistan policy if attacks against Chinese interests persist. For a Taliban government already struggling with economic collapse, sanctions, frozen assets and diplomatic isolation, alienating China would be a serious blow.

It is important to understand that China’s involvement in Afghanistan is not limited to abstract geopolitical interests. Beijing has eyed Afghanistan’s untapped mineral wealth, its potential role in regional connectivity, and its strategic location linking Central Asia, South Asia and the Middle East. However, all of this depends on one fundamental condition: internal security. The presence of militant groups such as Daesh, along with unresolved factional tensions within Afghanistan, undermines the Taliban’s claim that they have restored peace and order after decades of war.

The Taliban leadership often argues that insecurity is the result of external conspiracies or remnants of the previous regime. Yet the reality is far more complex. Militancy in Afghanistan today is not purely foreign-driven. Daesh-Khorasan has recruited locally, exploited ethnic and sectarian grievances, and targeted both Taliban officials and foreign nationals. The persistence of such attacks raises uncomfortable questions about the Taliban’s intelligence capabilities, internal cohesion, and ability to govern beyond the use of force.

This brings us to Pakistan, a country whose fate remains deeply intertwined with developments across the Durand Line. Pakistan has long maintained that stability in Afghanistan is essential for its own security. Over the years, Islamabad has repeatedly emphasized dialogue as the primary means of resolving disputes with Kabul, particularly on issues related to cross-border militancy. Yet despite sustained diplomatic engagement, backchannel contacts and public appeals for cooperation, Pakistan continues to face attacks allegedly planned or facilitated from Afghan soil.

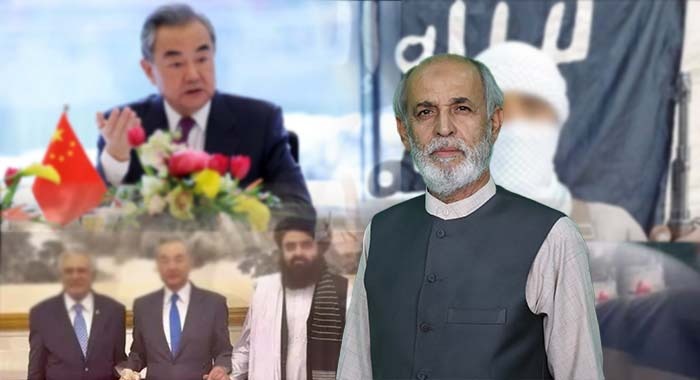

Sirajuddin Haqqani’s repeated calls for dialogue between Pakistan and Afghanistan must be viewed in this context. As the Taliban’s interior minister and a key figure within the Haqqani network, his statements carry weight. Haqqani has consistently argued that dialogue, not confrontation, is the only viable path forward for both countries. In principle, this position aligns with Pakistan’s long-standing policy. In practice, however, dialogue without concrete action has yielded little.

Pakistan’s experience over the past few years suggests that while talks have taken place, they have not translated into meaningful constraints on militant groups targeting Pakistan. This has led to growing frustration within Pakistan’s security establishment and public opinion. The fundamental question remains: dialogue with whom, and on what terms? If commitments made during talks are not enforced on the ground, dialogue risks becoming a delaying tactic rather than a solution.

At the same time, Pakistan itself is grappling with significant internal challenges. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the provincial government’s decision to launch protests from February 8 reflects a deepening political crisis. The stated objective of these protests is political pressure, particularly regarding the release of Imran Khan and demands for fresh elections. However, the broader implications of such agitation cannot be ignored, especially in a province already burdened by insecurity, economic hardship and humanitarian crises.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa today faces a convergence of crises: deteriorating law and order, shortages of flour, electricity and gas, and the ongoing impact of security operations in areas such as Tirah. Thousands of people have endured harsh winter conditions with inadequate shelter, while tragic incidents involving children underline the human cost of governance failures. In such circumstances, prolonged political protests risk diverting attention and resources away from urgent public needs.

The confrontation between the provincial government and the federal government further complicates matters. While the federal government has formed committees and signaled willingness to engage, negotiations remain stalled. History shows that protests can create pressure, but sustainable solutions ultimately require dialogue, compromise and institutional cooperation. Without this, political brinkmanship may exacerbate instability rather than resolve underlying grievances.

Returning to Afghanistan, the internal dynamics of the Taliban movement play a crucial role in shaping the country’s future. The often-discussed divide between Kandahar and Kabul is not merely geographical; it reflects competing visions of governance. The Kandahar faction, centered around the supreme leader, emphasizes rigid ideological control, strict social policies and resistance to external pressure. The Kabul faction, which includes figures such as Sirajuddin Haqqani, appears more pragmatic, aware of the need for international engagement and economic relief.

At present, real power rests in Kandahar. Decisions made by the supreme leader override those of ministers and technocrats in Kabul. This imbalance limits the ability of more moderate voices to influence policy, particularly on issues such as women’s education, media freedom and foreign relations. While some Taliban leaders privately acknowledge the costs of international isolation, they lack the authority to implement meaningful change.

This internal rigidity has profound consequences. Afghanistan remains diplomatically isolated, with only limited engagement from a handful of countries. Trade disruptions, including prolonged border closures with Pakistan, have further strained an already fragile economy. Ordinary Afghans bear the brunt of these policies, facing unemployment, food insecurity and restricted access to education, particularly for women and girls.

The restrictions on women’s education are especially damaging. By closing the doors of learning to half the population, the Taliban risk condemning an entire generation to marginalization. Beyond the moral and humanitarian dimensions, this policy undermines Afghanistan’s long-term economic prospects. No country can achieve sustainable development while systematically excluding women from education and the workforce.China, Russia and other regional actors may tolerate certain ideological differences, but they cannot ignore chronic instability and governance failures. Even Russia’s limited engagement with the Taliban has been cautious, reflecting lingering concerns about security and extremism. The message from the region is clear: Afghanistan must demonstrate responsible governance if it seeks meaningful integration into regional economic and political frameworks.

In this context, Sirajuddin Haqqani’s role becomes particularly significant. As a figure with influence, experience and international exposure, he is uniquely positioned to advocate for a more balanced approach. His calls for dialogue with Pakistan and respect for regional relationships suggest an understanding of Afghanistan’s strategic realities. However, rhetoric alone is insufficient. What is needed is the political courage to translate words into policy, even if that requires challenging entrenched positions within the Taliban leadership.

For Pakistan, continued engagement with Afghanistan remains necessary, but it must be grounded in realism. Dialogue should be tied to verifiable actions against militant groups, not merely promises. At the same time, Pakistan must address its own internal governance challenges, particularly in provinces like Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where public trust is eroding amid political turmoil and economic distress.

Ultimately, Afghanistan stands at a crossroads. The attack in Kabul that killed Chinese nationals is a warning sign, not only for Beijing but for the Taliban themselves. Persisting on a path of isolation, ideological rigidity and internal division will deepen Afghanistan’s and strain its relations with neighbors. Choosing engagement, reform and genuine cooperation offers a difficult but necessary alternative.

The region cannot afford another cycle of chaos emanating from Afghanistan. Stability there is not a favor to neighbors; it is a shared necessity. Whether the Taliban leadership recognizes this reality, and whether pragmatic voices within the movement can assert themselves, will determine Afghanistan’s trajectory in the years to come.