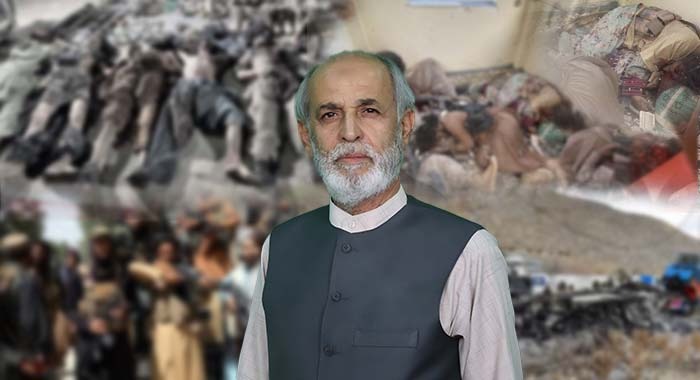

(Shamim Shahid)

The latest wave of coordinated terrorist attacks across multiple districts of Balochistan has once again forced Pakistan to confront an uncomfortable reality: despite repeated claims of improved security and operational success, the province remains deeply unstable. The near-simultaneous nature of these attacks, including incidents in Quetta the provincial capital followed by large-scale security operations, exposes not only the persistence of insurgent networks but also the structural weaknesses in Pakistan’s security and political approach to Balochistan.

Government statements following the attacks have been swift and predictable. Officials have pointed towards banned militant outfits as the operational executors of the violence, while the Defence Minister has gone a step further by directly blaming India for orchestrating or facilitating these attacks. While external involvement cannot be dismissed outright given the hostile regional environment and Pakistan’s adversarial relationship with India the more critical question remains unanswered: why does Balochistan continue to provide fertile ground for insurgency after more than seven decades of conflict, military operations, and political promises?

The insurgency in Balochistan is not a recent phenomenon, nor can it be reduced to isolated terrorist acts or foreign conspiracies alone. Its roots trace back to the late 1940s, when the question of Balochistan’s accession to Pakistan was contested by segments of the local leadership. Since then, the province has witnessed repeated cycles of armed resistance, negotiations, broken agreements, and military operations. From the early rebellions to the major insurgencies of the 1970s, and later the post-2000 phase that intensified after the killing of Nawab Akbar Bugti, the pattern has remained largely unchanged. Each phase has been marked by the use of force as the primary response, followed by limited political engagement that fails to address core grievances. The events unfolding today are not an anomaly; they are a continuation of this unresolved historical conflict.

What makes the recent attacks particularly alarming is not just their scale, but their timing and coordination. For months, official briefings suggested that militant networks in Balochistan had been weakened, their leadership neutralized, and their operational capacity significantly reduced. Yet the ability of armed groups to strike across twelve districts simultaneously openly displaying weapons, attacking sensitive locations, and briefly disrupting urban life stands in stark contrast to these assurances. This contradiction points to a serious intelligence failure. Repeated claims of “control” and “clearance” have created an illusion of stability that does not reflect ground realities. Intelligence assessments that underestimate insurgent capacity or overstate operational success only delay corrective action and deepen public distrust. When Quetta itself becomes a theatre of such activity, it raises legitimate questions about preparedness, coordination, and situational awareness at the highest levels.

The Defence Minister’s assertion that India is directly involved in fomenting violence in Balochistan aligns with Pakistan’s long-standing position that hostile foreign actors exploit internal fault lines. There is historical precedent for such interference, and regional rivalries make such actions plausible. Any state facing an adversary will attempt to exploit its weaknesses, and Pakistan is no exception. However, external involvement, even if proven, does not absolve the state of responsibility for internal conditions that make such interference possible. Foreign actors can only exploit grievances that already exist. They cannot manufacture decades of political alienation, economic deprivation, enforced disappearances, or the systematic exclusion of local voices from decision-making processes. Blaming India without simultaneously addressing domestic failures risks reducing a complex internal crisis to a simplistic external conspiracy.

Pakistan’s reliance on military operations as the primary tool to manage Balochistan has a long and troubled history. From the operations of the 1970s to more recent campaigns, the use of force has produced temporary calm but never lasting peace. Each operation has left behind social dislocation, resentment, and new generations willing to take up arms. The argument that “this time will be different” has been made repeatedly and disproven repeatedly. The harsh reality is that armed resistance cannot be permanently silenced through guns, checkpoints, or curfews. Voices suppressed by force resurface elsewhere, often more radicalized and more violent. Even after decades of military presence, the state cannot indefinitely govern Balochistan as a security zone detached from political processes.

The uncomfortable truth is that there is no military solution to the Balochistan problem. Any sustainable resolution must be political in nature, rooted in dialogue, trust-building, and the genuine inclusion of Baloch stakeholders. This is not a new idea. Multiple committees most notably those formed during the Musharraf era under Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain and later Shahid Hussain produced detailed recommendations addressing autonomy, resource control, and reconciliation. Unfortunately, these proposals were never fully implemented. Institutional resistance, lack of political will, and security-centric thinking ensured that reports gathered dust while the situation on the ground deteriorated. The cost of ignoring these recommendations is now being paid in blood and instability.

Supporters of the current approach often argue that Balochistan is politically represented, citing the presence of tribal leaders in government, parliament, and the provincial cabinet. While representation exists on paper, empowerment remains questionable. When key decisions regarding security, development, and resource allocation are made without meaningful local consent, political inclusion becomes symbolic rather than substantive.

True dialogue cannot be conducted at gunpoint, nor can it succeed if outcomes are predetermined. Negotiations must involve those who command influence on the ground, including voices that are currently marginalized or viewed solely through a security lens. Without this, any peace initiative will lack credibility.

The situation in Balochistan also finds echoes in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, particularly in Tirah Valley, where displacement, operations, and political blame games have deepened public frustration. The recent jirga-style gathering organized by the provincial government highlighted not only grievances over forced displacement but also the absence of coordinated policy between federal and provincial authorities. Thousands of families remain displaced, many unregistered, facing severe hardships. Announcements made through loudspeakers, sudden curfews, blocked roads, and delayed assistance have eroded trust. The subsequent finger-pointing between Islamabad and Peshawar has only reinforced the perception that ordinary citizens pay the price for institutional confusion and lack of accountability.

The tendency of federal and provincial governments to shift blame onto one another is counterproductive. In both Balochistan and KP, security decisions involve multiple stakeholders: civilian administrations, military commands, and intelligence agencies. When coordination fails, the consequences are borne by civilians, not institutions. Acknowledging failure is not a sign of weakness; it is a prerequisite for reform. Without honest introspection, policy corrections remain impossible. Admitting intelligence lapses, planning failures, and communication breakdowns is essential if future crises are to be avoided.

Pakistan still has a choice. It can continue down the familiar path of denial, force, and external blame or it can confront the political roots of its internal conflicts. Dialogue does not mean surrender, nor does political engagement equate to appeasement. It means recognizing that lasting stability cannot be imposed; it must be negotiated. If both sides demonstrate sincerity and commit to implementing agreed outcomes, progress is possible. History shows that conflicts rooted in political exclusion are resolved not through perpetual operations but through inclusive governance and credible reforms. Balochistan does not need another operation. It needs a new approach one that treats its people not as a security problem, but as equal citizens with legitimate rights and grievances. Until that shift occurs, Pakistan will continue to fight the same battles, suffer the same losses, and ask the same questions without ever finding lasting answers.