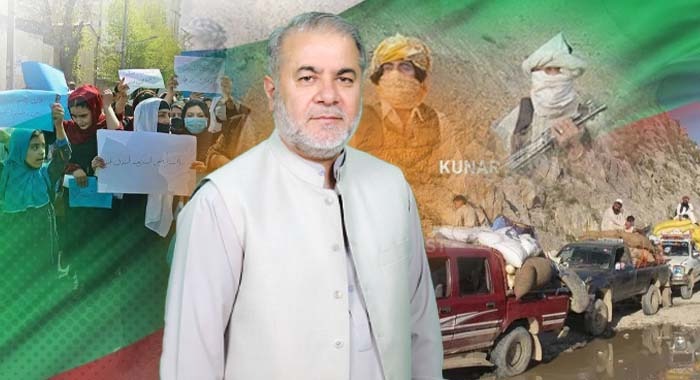

I am often asked whether Afghanistan is witnessing a new political turn or whether the developments we are seeing are merely cosmetic. From the outside, it may appear that the Taliban are divided into two camps, the so-called Kandahar group and the Kabul group. One is associated with rigid policies, strict social controls, and an uncompromising worldview. The other is portrayed as comparatively pragmatic, interested in external engagement and maintaining some alignment with the global community. These perceptions raise many questions, but to understand today’s realities, context matters.

The banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan did not emerge overnight. It began as a collection of small militant factions that came together in December 2007 in Miran Shah, North Waziristan. At that meeting, these groups unified under a single umbrella, pledging allegiance to Baitullah Mehsud, who became the first Ameer of the TTP. Fighters from Swat to Waziristan joined this alliance, committing themselves to armed confrontation with the Pakistani state and agreeing that no faction would negotiate independently.

What followed was an intense wave of violence. Militants descended from the mountains into major cities. Karachi airport was attacked. Lahore and Islamabad were hit. The scale and frequency of attacks left Pakistan with little choice but to launch military operations across Swat, Buner, Mohmand, and Waziristan.

Within this structure, Umar Khalid Khurasani, originally from Mohmand district, emerged as a key commander. He led the TTP in Mohmand and was responsible for deadly attacks in Peshawar, Charsadda, and his home district. Despite his seniority, serious differences developed between him and the TTP leadership. He became the first major commander to break away and went on to form Jamaat-ul-Ahrar.

Although Jamaat-ul-Ahrar never had large numbers, its fighters were highly trained and well-funded, particularly through revenues from marble mines. After the launch of Operation Zarb-e-Azb in 2014, its members relocated to Afghanistan. The group later rejoined the TTP briefly, but once negotiations with Pakistan began, Khurasani again parted ways. He was eventually killed in an IED attack in Afghanistan, yet his group remains active. It may be weaker today, but it continues to pose a serious threat, especially in border districts like Mohmand.

Recent reports that dozens of militants from Swat have joined Jamaat-ul-Ahrar are deeply concerning. Historically, the TTP leadership was dominated by the Mehsud tribe. When Maulana Fazlullah from Swat became chief, many within the group believed the organization weakened. Since Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud took over, the TTP has regained operational strength. This has bred resentment among militants from Swat, who feel sidelined as activity intensifies in Waziristan and southern districts. Even so, the TTP remains far more dominant than Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, which is unlikely to fill that space in Swat or Malakand.

Much is also made of supposed rifts within the Afghan Taliban. Audio leaks and internal arguments are often cited as proof of an impending split. I have heard these recordings. Differences do exist, particularly over issues such as girls’ education, media restrictions, and governance. However, these disagreements should not be exaggerated.

When people speak of the Kandahar group, they refer to leadership under Sheikh Hibatullah Akhundzada, alongside figures like Abdul Ghani Baradar and Prime Minister Mullah Hassan Akhund. The Kabul group is commonly associated with Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani and the intelligence leadership. Many Taliban are unhappy with current policies, but they understand one thing clearly: internal confrontation would only benefit external actors. A public split could mean total collapse. That is why dissent remains contained.

No one within the movement has the capacity to openly challenge Sheikh Hibatullah. Real divisions would only become visible if he were to remove figures like Sirajuddin Haqqani. Until then, complaints will remain internal.

Afghanistan today faces immense hardship. Unemployment is widespread. Inflation is high. Media operates under severe restrictions. Journalists cannot independently verify or quote sources after attacks and must rely solely on official statements. Institutionally, the country remains fragile. There is no national army, no coherent administrative structure, and little public or regional confidence in the system’s longevity.

This instability has direct implications for Pakistan. Border regions like Tirah, adjacent to Afghanistan’s Nangarhar province, host multiple militant groups, including the banned TTP, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, Lashkar-e-Islam, ISKP, and factions aligned with Hafiz Gul Bahadur. These groups are well financed, drawing income from opium in Afghanistan and marble mining in Pakistan.

On the economic front, Afghanistan’s turn toward Iran and the Chabahar Port is understandable. With key border crossings with Pakistan frequently closed, Kabul has little choice. India’s heavy investment in Chabahar has strengthened Iran-Afghanistan ties and shifted trade routes accordingly.

Turning to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the state of governance is deeply troubling. Three months into office, Chief Minister Sohail Afridi has shown little interest in provincial administration. Cabinet meetings are postponed or conducted remotely while he remains outside the province, following the same pattern set by his predecessor. With key portfolios concentrated in his hands, his absence effectively paralyzes governance.

Development, planning, and service delivery have been sidelined. The provincial bureaucracy continues to function out of necessity, not political leadership. Travel to Lahore and Karachi has yielded nothing tangible for the province. Cabinet decisions remain pending. Yet the political leadership appears unconcerned.

Within PTI, performance has become irrelevant. Loyalty is measured not by governance but by rhetoric, confrontation, and proximity to Imran Khan’s name. Office attendance, project execution, and public service no longer matter. What matters is visibility, slogans, and hostility toward opponents.

As for Imran Khan’s imprisonment, the reality is uncomfortable. Neither the previous nor the current provincial leadership genuinely wants him released. His absence allows power to remain uncontested. When he was active, ministers were held accountable. Today, his name is sufficient currency for elections, offices, and influence.

Imran Khan was never a traditional politician. He made serious mistakes and continues to do so. More critically, he surrounded himself with individuals who used him rather than served him. The present arrangement suits everyone involved. That is why the drama continues.