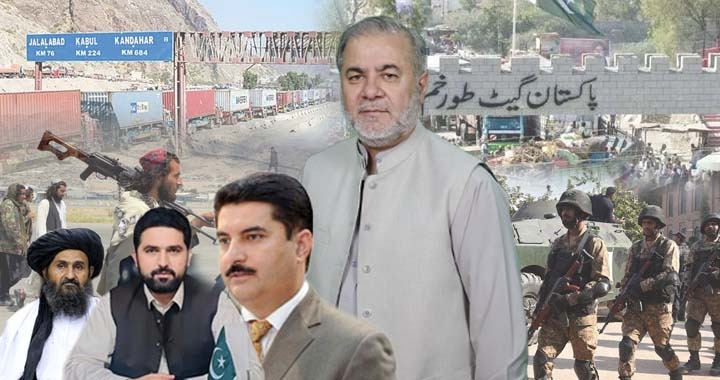

For months the relationship between Pakistan and the Afghan Taliban has been strained by mistrust, miscommunication and persistent cross border militancy. Now Russia has joined Iran, China and Turkey in proposing to mediate between the two countries. This development has created new debate about whether outside facilitation can lower tensions or whether deeper political issues still need to be confronted directly by Islamabad and Kabul.

Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s announcement of a three month deadline to end dependence on Pakistani trade routes has further complicated an already sensitive situation. The Afghan interim government is looking for alternate corridors and has used charged language that has contributed to an emotional and counterproductive environment. Although trade routes are centuries old and interdependent, an abrupt attempt to sever ties harms ordinary people on both sides. Afghan households rely heavily on lower cost Pakistani commodities such as cement, steel, vegetables and fruit. Pakistani livelihoods are equally connected to this cross border movement of goods.

Afghanistan is the eighth largest market for Pakistan. It absorbs a significant volume of agricultural produce that rural Pakistani communities depend upon. A truck that leaves Lahore in the morning reaches Jalalabad by evening, which lowers transport cost and makes life easier for Afghan buyers. Poverty exists on both sides of the border and no country can afford to politicise the affordability of food and essential items. Emotional decisions from Kabul ignore this economic reality and create unnecessary strain.

A Political Rift Fueled by Rumours, Port Politics and Regional Actors

There are many regional actors involved in Afghanistan. This has often made Afghans believe that Pakistan opposes them, although there is no public evidence that Pakistanis carry such hostility. Pakistan has hosted Afghan refugees for decades and has never prevented Afghans from running restaurants, shops or businesses. The people of Pakistan wish for stability and prosperity in Afghanistan because peace across the border benefits both societies.

Russia’s proposal to mediate is therefore a positive development. Though the Afghan interim government has not been recognised internationally, Pakistan has still chosen dialogue. Meetings in Doha and Istanbul failed to yield breakthroughs but they created channels for discussion. Russia’s willingness to facilitate talks undermines conspiracy theories that outside powers are trying to push Pakistan and Afghan Taliban toward confrontation to seize strategic sites like Bagram. Moscow would not involve itself in mediation if Washington were allegedly manipulating the situation from behind the scenes.

Iran also acts according to its interests. Afghan trade has shifted heavily to Bandar Abbas and Chahbahar, crowding Iran’s ports and benefiting its economy. Every state looks after its own interests. China wants stability because of its investments. Turkey and Qatar desire regional calm. No country is acting as a brother. They are all acting as rational powers seeking stability for their own strategic and economic reasons. Pakistan’s geographic and nuclear stature ensures that none of these actors want confrontation in the region.

Trade, Smuggling and the Persistent Narco Politico Terror Nexus

The Tirah Valley continues to suffer from a complex mix of narcotics trafficking, illegal trade and militancy. Smuggling remains far greater in volume than official trade. Despite fencing efforts, the border remains porous because of difficult terrain and repeated damage to the fence. Entry and exit are still possible at many points. Weapons abandoned by the United States in Afghanistan have spread to every corner of Pakistan through this illegal network. Markets in Sindh, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa now contain stockpiles of such weapons.

Narcotics, arms smuggling and mineral extortion remain deeply entrenched because powerful and influential groups are involved on both sides of the border. Extortion from mining operations in the tribal districts continues. Smuggling routes, seasonal patterns and profit margins are well known to old networks. No government has attempted a sincere and sustained effort to dismantle these structures. A border of this length and difficulty requires advanced management with properly organised entry points, regulated movement and robust administration, which neither side has been able to enforce.

KP’s Security Shift and the Risks of Politicising Terrorism

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government’s decision to revoke Action in Aid of Civil Power and bring CTD and police to the front line raises serious questions. CTD is an intelligence based special operations body, not a force structured for prolonged ground combat. Proper assessment of manpower, equipment and resources is essential. Security cannot be improved through political slogans or administrative gestures. Terrorism is a national threat, not a provincial talking point.

The KP chief minister and his team need to sit with federal authorities, military leadership and all relevant institutions. Concerns must be shared openly. A committee representing all political parties should have been formed after the assembly’s jirga. It should have engaged GHQ, the corps command and the prime minister. Unity is essential. Pakistan has been fighting terrorism for more than two decades. New options must be explored with dialogue, coordination and trust rather than political confrontation.