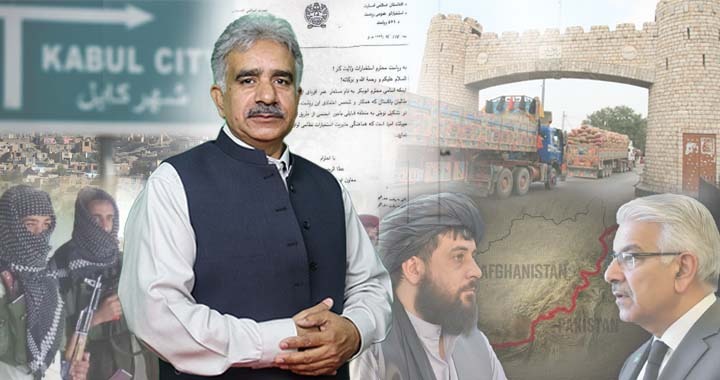

The evidence is mounting, and it is disturbing in its clarity: elements inside Kabul’s current administration are not merely tolerating anti-Pakistan groups, they are actively facilitating them. This is not idle speculation. Our security agencies and foreign office have repeatedly presented material; now we have direct, operational evidence, letters from within Afghan intelligence channels, that demand a decisive response.

One such communication, attributed to Atta-ur-Rehman Abid of Upper Tapi (code 591), instructs handlers in Kunar to facilitate the border crossing of a senior TTP commander named Abu Bakr, along with 25 fighters, into Bajaur. Another letter, from Maulvi Karimullah, similarly requests help moving Muhammad Naeem, son of Abdul Salam, with six associates. These are not generic warnings; they are logistics orders asking for passage, shelter and support. If these documents are genuine, they point to state-level facilitation of cross-border militant movement.

Let us be blunt about what this means. The Afghan Taliban regime’s rhetorical posture; recasting militant actors as political opponents rather than terrorists, produces a practical outcome: sanctuary, finance and freedom of movement. Denial of terrorist identity equals de facto shelter. That is not semantics, it is sponsorship. And sponsorship turns border villages into staging grounds for attacks on our soil.

We have seen the consequence on the ground. Commanders of significance, Qari Amjad, reported second-in-command under Mufti Noor Wali Mehsud, and an IS-KP commander named Hizam, were killed while trying to infiltrate from across the border. These incidents confirm a pattern: militants attempt to use Afghan terrain and networks to strike into Pakistan, and when pressure mounts, Kabul’s response has been inadequate or, worse, complicit. The mountains and the fog of war provide deniability; that deniability is being weaponised.

Faced with this, Pakistan needs unity and clarity. Instead, what we are witnessing inside Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is fragmentation and political calculation. The KP leadership has not been on the same page as the federal government on tackling terrorism and extremism. That dissonance dilutes our national posture and hands talking points to hostile actors and foreign propaganda outlets. The Afghan Taliban’s spokesperson has already exploited this divide, claiming KP is against operations; Indian and Afghan social media have amplified the narrative. Whether true or not, the damage is real.

Worse still, provincial politics increasingly treats security as a lever. Afghan refugees are trotted out as instruments of pressure on the centre. Talks with the Taliban and TTP are presented as options not strictly for peace, but as political cards to be played in service of domestic aims; the release of their ‘Bani’, claims of a stolen mandate, demands to reclaim political power. When security operations become bargaining chips, the priorities shift from protecting citizens to theatrical bargaining.

The recent call for a provincial security committee meeting underscores this problem. KP already has forums for coordination: the National Security Council, the Apex Committee, and direct federal-provincial channels. If the province has constructive proposals, those fora exist. Instead, we see invitations to broad party meetings and grandstanding that duplicates mechanisms already in place — delays dressed as engagement.

A further and darker dimension raised during recent briefings is the nexus between terrorism and drug trafficking in Tirah and parts of Khyber district. The DG ISPR pointed to links between militancy and smuggling routes; while names were not spoken, the implication was unmistakable: local political and commercial elites are embedded in profit networks that fuel instability. Bara’s open markets, the centuries-old trafficking patterns, and vast opium cultivation nearby create an economy that insurgents and traffickers exploit. When political protection shields those networks, operations meet resistance not because of principle but because of patronage.

That political protection explains why the province complains of capacity while appearing unwilling to act. “We have security forces on the border,” some argue — and indeed, smuggling is global and difficult to eliminate. But inability cannot be an excuse for inaction or for hiding behind communal ties. When the rationale becomes “they are our people,” the rule of law collapses into selective protection. If the people implicated in these networks are truly “ours,” then the state has a duty to enforce the law impartially, not to shelter criminals for political expedience.

There is a diplomatic avenue worth pursuing: the talks scheduled for November 6 under Turkish and Qatari auspices could deliver a mechanism to verify and deter cross-border infiltration. But success requires hard details, not platitudes. Who judges infiltration? How will verification work? What penalties are imposed, and who guarantees compliance? Pakistan has suggested Saudi Arabia as guarantor; the Taliban seeks U.S. involvement. Each actor brings its own agenda. If the Istanbul talks merely paper over contradictions, they will have bought only time for perpetrators.

Let us be clear: talks are not an alternative to action. They are complementary to credible enforcement. Warfare alone is not the answer; honest diplomacy is necessary. But diplomacy without enforceable mechanisms, and politics that undermine operational unity at home, will hand the battlefield to militants and the narrative to our adversaries.

KP’s leadership must choose: be a partner in national security, or remain an instrument of pressure politics. Using refugees, negotiations and operations as bargaining chips is unconscionable when men and women die on our frontlines. The evidence from Afghan intelligence channels, from battlefield eliminations, and from internal briefings is consistent: insurgents are being enabled, and political convenience is blunting our response.

If the province genuinely stands with the armed forces, it will stop politicising security, present workable proposals through established national mechanisms, and cooperate fully to close routes that feed terror. That requires courage to confront vested interests at home and honesty to explain sacrifices to the public. Until then, the only beneficiaries of this strategy will be traffickers, militant facilitators and political actors who profit from disorder, while ordinary citizens and frontline officers pay the price.

If fights and operations were the sole answer, every problem would already be solved. They are not. Wars and raids alone cannot deliver lasting peace. What we need alongside force is clear, objective talks; negotiations that are honest, enforceable and aimed at real solutions. If those talks can produce mechanisms for verification, penalties and guarantees, they will strengthen deterrence and reduce bloodshed.

But there is a warning in plain language: if these talks fail to yield concrete results, if participants cannot agree on the fundamentals — what constitutes cross-border infiltration, how violations will be verified, and who will enforce penalties — then the temporary calm will evaporate and the problems will only grow worse. That is the sobering choice before us: pursue disciplined diplomacy backed by action, or accept a future with more violence and more suffering.