Mushtaq Yusufzai

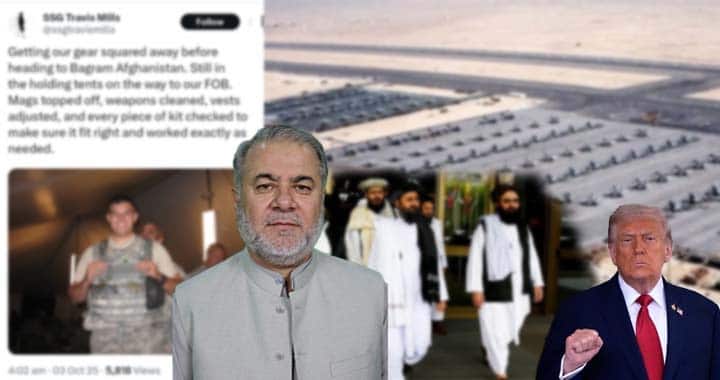

In recent days, social media platforms have been abuzz with speculation that the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is considering handing over the Bagram Airbase to the United States. These rumours, which spread rapidly across various outlets, have once again reignited debates about American interests in the region and the internal stability of the Taliban government. Having closely followed Afghanistan’s political and security developments for decades, I can confidently say that while the rumours have gained momentum, there is little substance to support them.

The speculation gained traction when former US President Donald Trump, during an address in London, remarked that Washington was exploring ways to “regain control” of the Bagram Airbase citing its strategic proximity to China and the growing Chinese presence in the region. His comments, though vague, were enough to fuel widespread conjecture in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries. For Afghans, Bagram is not just a military installation; it symbolizes the two-decade-long US presence that defined their country’s modern history. The base, often referred to as “mini-America,” served as the nerve centre of US-led operations against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda.

The Taliban government, however, has repeatedly denied any such plans. Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi has on multiple occasions clarified that handing over Bagram or any part of Afghan territory to foreign forces is out of the question. Yet, the Afghan government’s recent silence on these renewed rumours has raised eyebrows, leading some to suspect there might be more than meets the eye. But after speaking to reliable sources within the Taliban, it is clear that these speculations are unfounded. According to them, repeatedly addressing baseless rumours only amplifies them further a stance that has allowed misinformation to flourish online.

To understand why this rumour resonates so strongly, one must remember that Bagram is deeply symbolic. If the Taliban were to allow the US any form of military access there, it would be political suicide for the Islamic Emirate. Such a move would trigger widespread outrage, not only within Afghanistan but also among Taliban fighters and ideological hardliners who sacrificed for decades to expel foreign forces. It could ignite an internal rebellion and plunge the country back into chaos. The Emirate, already facing economic isolation and internal disagreements, cannot afford such an existential crisis.

This brings us to another topic dominating Afghan discourse the reported rifts between the Taliban’s Kandahar-based leadership and its Kabul faction, often associated with the Haqqani Network. Historically, the Taliban movement was born in Kandahar under the leadership of Mullah Omar, and it continues to draw its ideological strength from the region. The current Supreme Leader, Sheikh Hibatullah Akhundzada, also resides there and exercises authority primarily through spiritual and doctrinal influence.

On the other hand, Sirajuddin Haqqani the influential Interior Minister and son of veteran jihad commander Jalaluddin Haqqani represents a more pragmatic and politically active faction based in Kabul. His network played a decisive role in the Taliban’s military victory, particularly in urban warfare and operations against the US and Afghan forces. Over the years, the Haqqani faction’s operational discipline and influence have made it indispensable to the Emirate’s internal structure.

Reports surfaced recently that Haqqani travelled to Kandahar to meet the Supreme Leader but was denied an audience, prompting rumours of a power struggle. My own communication with both sides suggests otherwise. While there are ideological and generational differences within the movement — particularly over issues such as women’s education and engagement with the international community there is no evidence of an immediate schism. Younger Taliban officials do express frustration at the rigid policies emanating from Kandahar, but these disagreements, at least for now, remain within manageable limits.

That said, Afghanistan today is a fragile mosaic of competing interests, mistrust, and historical grievances. The country remains awash with weapons an estimated 100,000 to 500,000 arms left behind by NATO forces. Should the Taliban leadership fracture, these weapons could easily fuel internecine warfare, plunging Afghanistan into another devastating civil conflict.

Adding to the confusion are incidents such as the sudden nationwide internet blackout on September 29. The outage, which lasted several hours, cut Afghanistan off from the world, leaving journalists and citizens alike in the dark. The timing coincided with the height of the Bagram rumours, giving rise to wild speculation that the US had reoccupied the airbase or that an internal coup was underway. The Taliban later attributed the blackout to “technical reasons” and ageing fiber-optic cables, though this explanation failed to convince many observers. Some officials claimed the shutdown was linked to efforts to curb the sale of data networks to foreign entities. Yet, even senior Taliban figures admitted privately that they were unaware of the disruption’s cause a rare moment that highlighted the opacity and communication gaps within the regime.

Interestingly, the blackout also revealed another truth: the Pakistani Taliban’s online presence operates primarily from Afghan soil. When Afghanistan went offline, several Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) accounts went silent simultaneously, confirming what Islamabad has long alleged that the TTP’s digital infrastructure is being hosted and coordinated from Afghanistan.

In conclusion, while rumours about Bagram Airbase continue to capture the imagination of social media users, they remain exactly that rumours. The Islamic Emirate, despite internal ideological divisions and governance challenges, is unlikely to make a decision that would endanger its own survival. The silence of Kabul officials should not be mistaken for complicity but rather reflects the Emirate’s traditional approach of avoiding engagement with external narratives it deems hostile.

What Afghanistan truly needs at this juncture is stability, transparency, and a clear vision for governance not another cycle of rumours and misinformation that can drag the country back into the abyss of uncertainty.