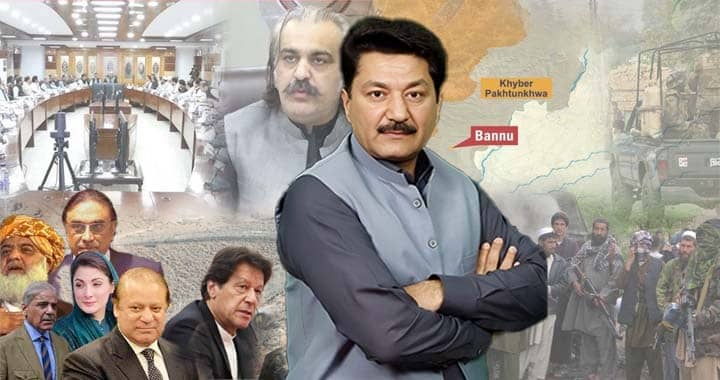

At a time when Pakistan’s security forces are laying down their lives in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) to defend the motherland, the political and administrative disconnect in the province is not just troubling—it is alarming. The gravity of the security situation demands national unity, institutional cohesion, and a shared resolve. Unfortunately, what we’re witnessing instead is political fragmentation, blame games, and a dangerous vacuum in leadership at both the provincial and federal levels.

It is critical to recognise that terrorism is not a provincial law and order issue that can be tackled by a solitary police force or a single tier of government. The groups operating in KP and bordering regions are not dacoits or street criminals; they are transnational militant networks with sophisticated infrastructure, foreign sanctuaries, and ideological motivations that transcend provincial jurisdictions.

Expecting the provincial government alone to neutralise such threats is both unfair and strategically flawed. Border protection is a federal domain, and coordination between security institutions; the Pakistan Army, FC, CTD, police, intelligence agencies, and civilian leadership, is essential. Terrorism is a challenge to the state, not just a provincial administration.

The present political landscape reflects a stark lack of coherence. With different political parties in power at the Centre and in KP, even a national security crisis like terrorism becomes entangled in political narratives. This politicisation weakens public trust, paralyses swift decision-making, and benefits the very actors we are trying to fight.

There are critical issues where politics must stop and patriotism must begin, and terrorism is foremost among them. The state cannot afford to appear divided in the face of such a grave threat. It emboldens militants and demoralises citizens, especially those in the worst-affected regions of South KP, Bajaur, Waziristan, and Dir.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the current crisis is the two very different realities experienced across Pakistan. Urban centres like Islamabad, Lahore, and Karachi enjoy relative peace and liberty. Meanwhile, in parts of KP, civilians cannot leave their homes after dusk. Hospitals are inaccessible at night. Police presence disappears after dark. There is a silent curfew imposed by fear.

In the tribal districts and southern KP, residents are effectively trapped in their homes as soon as the sun sets, while the rest of the country enjoys night-time recreation and comfort. This geographic disparity in safety reflects a larger failure of governance and accountability.

Why does Pakistan, more than any other neighbouring country, continue to be targeted by groups claiming to wage “Jihad”? The answer lies in both geography and history.

Pakistan shares a porous and mountainous border with Afghanistan—an area marked by ethnic, cultural, and linguistic similarities. This terrain, combined with familial and tribal ties across the border, makes infiltration, sheltering, and guerrilla tactics easier for militants. Unlike in China, Iran, or Tajikistan, there are no hard language or cultural barriers in KP or Balochistan to obstruct these actors.

Moreover, the so-called success of the Afghan Taliban against U.S. and NATO forces has emboldened various regional extremist factions. They mistakenly believe that if the Taliban could defeat global powers, they too can challenge the Pakistani state. But they forget that the comparison is fundamentally flawed. Pakistan is not a foreign occupier—it is their own nation, which has historically supported Afghan refugees and even the Taliban cause at great cost.

Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan’s recent offer of talks on Pakistani soil raises significant questions. The TTP’s leadership insists they are in Pakistan, not Afghanistan—a narrative aimed at deflecting international pressure from the Afghan Taliban.

Pakistan has repeatedly maintained that these terrorists operate from Afghan territory. This claim is not without substance; cross-border raids, hideouts, and safe havens have been well-documented. The current pressure on the Afghan Taliban to rein in these elements is not just from Islamabad, but also from Iran, China, Russia, and Central Asian states affected by similar threats, such as Daesh-Khorasan and ETIM.

This growing regional pressure may be compelling the TTP to reconsider its strategy. However, past peace deals with such groups have ended in betrayal. Ceasefires have been short-lived, followed by waves of fresh attacks. Pakistan must therefore approach any new negotiation proposal with caution, strength, and clear terms that uphold the state’s sovereignty and security.

Pakistan has the military capability and the right to respond to cross-border terrorism. In fact, it has already conducted targeted operations in Afghan border provinces like Khost, Paktia, and Nangarhar. These strikes have sent a strong message: if the Afghan Taliban fail to control or expel these groups, Pakistan will act unilaterally.

Any suggestion that Pakistan will hesitate to strike militant hideouts, even in Kabul, underestimates the resolve of the state. However, such actions must be carefully calculated to avoid diplomatic fallout and ensure regional stability.

The most visible; and shameful, failure is the absence of KP’s civilian leadership in mourning and crisis. Funeral prayers of martyred soldiers go unattended. The wounded are ignored. Families of the fallen are left alone. Symbolism matters, and silence from the top only deepens the despair of those on the front-lines.

The provincial government cannot afford to remain politically aloof while its people suffer and security forces bleed. It must show presence, solidarity, and an active role in governance—even as terrorism is addressed through a unified national effort.

Pakistan’s internal stability is under threat from actors who seek to exploit our divisions. Whether it is the TTP, Daesh, or BLA, their goal is singular: to weaken the state by sowing chaos. Our response must be just as singular—national unity, not political scoring; institutional coordination, not blame-shifting.

The time for statements and condemnations is over. What is needed now is a cohesive, robust, and nation-backed response to terrorism—before more lives are lost, and more regions are plunged into darkness.